Most 3D printers use leadscrews for at least one axis. These are simple devices that are essentially a steel screw thread and a brass nut that travels on it. However, for maximum precision, you’d like to use a ball screw. These are usually very expensive but have many advantages over a leadscrew. [MirageC] found cheaper ball screws but, since they were inexpensive, they had certain limitations. He designed a simple device that improves the performance of these cheap ball screws.

Superficially, a ball screw looks like a leadscrew with an odd-looking thread. However, the nut is very different. Inside the nut are ball bearings that fit in the grooves and allows the nut to spin around with much less friction. A special path collects the ball bearings and recirculates them to the other side of the nut. In general, ball screws are very durable, can handle higher loads and higher speeds, and require less maintenance. Unlike leadscrews, they are more expensive and are usually quite rigid. They are also a bit noisier, though.

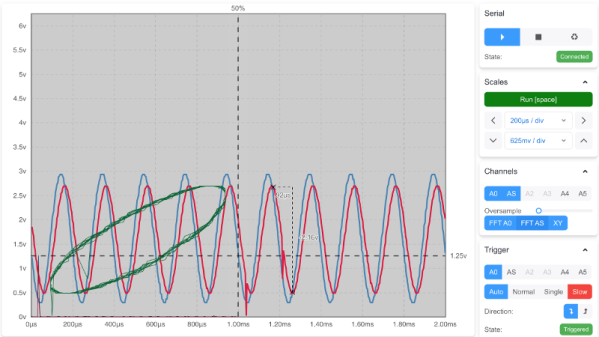

Ball screws are rated C0 to C10 precision where C10 is the least accurate and the price goes up — way up — with accuracy. [MirageC] shows how cheaper ball screws can be rolled instead of precision ground. These screws are cheaper and harder, but exhibit more runout than a precision screw.

This runout caused wobble during 3D printing that was immediately obvious on the prints. Using a machinist’s dial gauge, [MirageC] found the screws were not straight at all and that even a relatively poor C7 ball screw would be more precise.

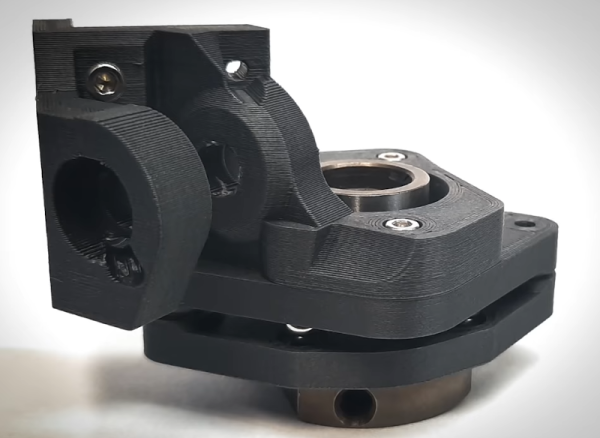

The solution? A clever arrangement of 3D printed parts. ball bearings, and magnets. The device allows the nut to move laterally without transmitting it to the print bed. It is a clever design and seems to work well.