It’s an auspicious moment for retrocomputing fans, as it’s now four decades since the launch of the Sinclair ZX Spectrum. This budget British microcomputer was never the best of the bunch, but its runaway success and consequent huge software library made it the home computer to own in the UK. Here in 2022 it may live on only in 1980s nostalgia, but its legacy extends far beyond that as it provided an entire generation of tech-inclined youngsters with an affordable tool that would get them started on a lifetime of computing.

What Was 1982 Really Like?

There’s a popular meme among retro enthusiasts that the 1980s was a riot of colour, pixel artwork, synth music, and kitschy design. The reality was of growing up amid the shabby remnants of the 1970s with occasional glimpses of an exciting ’80s future. This was especially true for a tech-inclined early teen, as at the start of 1982 the home computer market had not yet reached its full mass-market potential. There were plenty of machines on offer but the exciting ones were the sole preserve of adults or kids with rich parents. Budget machines such as Sinclair’s ZX81 could give a taste of what was possible, but their technical limitations would soon become obvious to the experimenter.

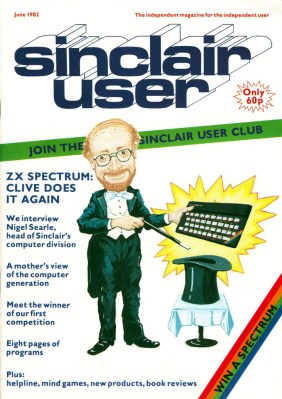

1982 was going to change all that, with great excitement surrounding three machines. Here in the UK, the Acorn BBC Micro had been launched in December ’81, the Commodore 64 at the start of ’82, and here was Sinclair coming along with their answer in the form of first the rumour of a ZX82, and then the reality in the form of the Spectrum.

This new breed of machines all had a respectable quantity of memory, high-res (for the time!) colour graphics, and most importantly, sound. The BBC Micro was destined to be the school computer of choice and the 64 was the one everybody wanted, but the Spectrum was the machine you could reasonably expect to get if you managed to persuade your parents how educational it was going to be, because it was the cheapest at £125 (£470 in today’s money, or about $615). Continue reading “The Sinclair ZX Spectrum Turns 40”