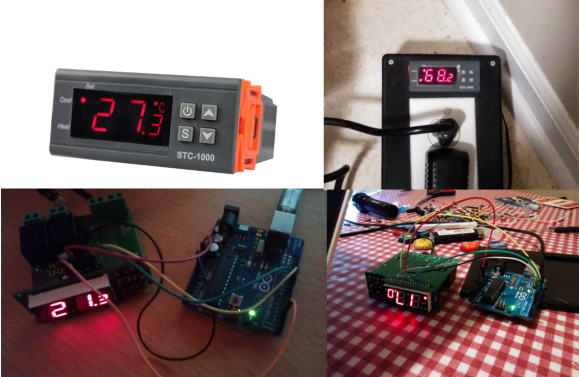

Beer lovers rejoice! [Mats] has reverse engineered a temperature controller and written new open source firmware for it. This effectively gives all us homebrewers a low cost, open source software driven controller. The STC-1000 is a cheap (under $20 USD) temperature controller mass-produced in the far east. The controllers do work, but have several limitations. The programming options are somewhat limited to basic set points for heat and cool. The controller also is only programmed for temperature display in Celsius, which is a bit of an annoyance for those of us who think in Fahrenheit. Under the hood, the STC-1000 utilizes a Microchip PIC16F1828 microcontroller. Unfortunately the PIC’s protection bits were set, so the original code would have been extremely difficult to extract. Not a problem, as [Mats] reverse engineered the hardware and wrote his own firmware. A 10k NTC thermister acts as the temperature probe. The probe is read by the PIC’s ADC. These probes are not very linear, so a look up table is used to convert from volts to degrees Celsius or Fahrenheit.

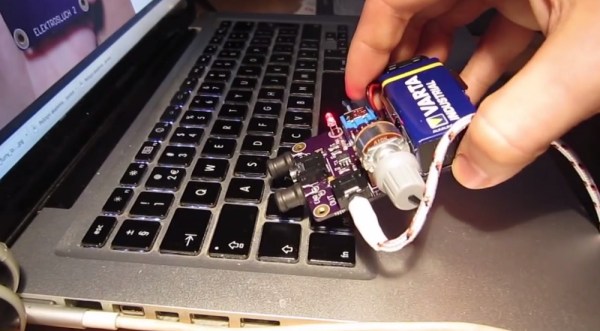

[Mats] new firmware allows for up to 6 profiles. Each profile has up to 10 set points and a time duration to hold each of the set points. Hysteresis and temperature offset values are also programmable via the front panel. PIC software is often written in C using Microchip’s MPLAB tool chain, and programmed with the PICkit 3 In Circuit Serial Programming (ICSP) tool. [Mats] decided to buck the system and wrote his C code using Small Device C Compiler. To keep things simple for homebrewers who may not have Microchip tools, [Mats] used an Arduino Uno for flashing duties. Thankfully the unholy matrimony of a PIC and an AVR has not yet caused a rift in time and space. The firmware is still very much in the beta stage, so if you want to help out, join the discussion on the homebrew talk forum. If you see [Mats] tell him we owe him a Haduino which he can use to almost open his beer.

[Thanks for the tip Parker!]

Welcome to Droning On, Hackaday’s new column covering all things unmanned. In this column we will primarily focus on aerial vehicles, both fixed and rotary wing. Expect to see traditional R/C, as well as First Person View (FPV) models, computer controlled autopilot systems, as well as anything new that shows up on our radar.

Welcome to Droning On, Hackaday’s new column covering all things unmanned. In this column we will primarily focus on aerial vehicles, both fixed and rotary wing. Expect to see traditional R/C, as well as First Person View (FPV) models, computer controlled autopilot systems, as well as anything new that shows up on our radar.