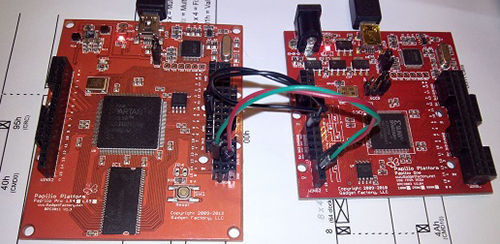

Although it’s derided for not being open source, EagleCAD is an extremely popular piece of schematic and PCB layout software. Most of the popularity is probably due to the incredible amount of part libraries – it’s certainly not the features Eagle has to offer or its horrible scripting capabilities. [Rob] had enough of the lack of good scripting support in Eagle, so he’s been spending his time making Eagle’s ULP work with Python. He’s only been at it a short time, but already it’s much more usable than the usual Eagle scripts.

Although it’s derided for not being open source, EagleCAD is an extremely popular piece of schematic and PCB layout software. Most of the popularity is probably due to the incredible amount of part libraries – it’s certainly not the features Eagle has to offer or its horrible scripting capabilities. [Rob] had enough of the lack of good scripting support in Eagle, so he’s been spending his time making Eagle’s ULP work with Python. He’s only been at it a short time, but already it’s much more usable than the usual Eagle scripts.

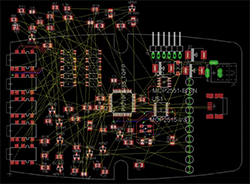

Below you can check out a pair of videos of [Rob]’s Python tools for Eagle in action. The first video goes through aligning a few symbols and creating a board outline (with proper curves!) from a DXF file. The second video shows exactly how valuable these tools are when laying out a board: imagine hundreds of LEDs and resistors automatically aligned to each other with a single click of a mouse. Beautiful.

All the PyEagle stuff is available on [Rob]’s github, with a DXF importer, group manager, and alignment tool included. Now that everything’s Python, it’s easy to build your own tools without relying on Eagle’s odd ULP language.