Circuit-bending is tons of fun. The basic idea is that you take parts of any old electronic device, say a cheap toy keyboard, and probe all around with wires and resistors, disturbing its normal functioning and hoping to get something cool. And then you make art or music or whatever out of it. But that’s a lot of work. What you really need is a circuit-bending robot!

Or at least that’s what [Gijs Gieskes] needed, when he took apart a horrible Casio SA-5 and grafted on enough automatic glitching circuitry to turn it into a self-playing musical sculpture. It’s random, but somehow it’s musical. It’s great stuff. Check out the video below to see what we mean.

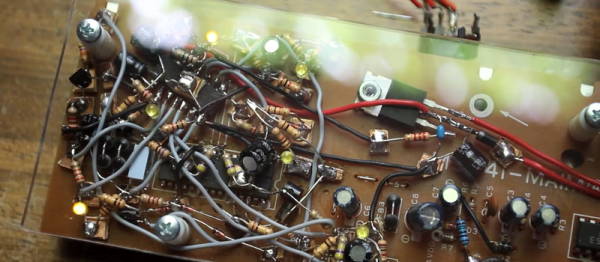

We also love the way the autonomous glitching circuit is just laid over the top of the original circuitboard. It looks like some parasite out of Aliens. But with blinking LEDs.