The problem with click-bait titles, besides the fact that they make the reader feel cheated and maybe a little bit dirty for reading the article, is that they leave us with nothing to say when something is truly outstanding. But the video of [Tiburcio de la Carcova] building up a mini-Galaga cabinet (complete with actual tiny CRT screen from an old portable 5″ TV) is actually the best we’ve ever seen.

Plywood is laser-cut. Custom 3D printed parts are manufactured and assembled, including the joysticks and coin door. Aluminum panels are cut on a bandsaw and bent with a hand brake. Parts are super-glued. In short, it’s a complete, sped-up video of the cutting-edge of modern DIY fab. If that’s not enough reason to spend four minutes of your time, we don’t know what is.

[Tiburcio] has also made a mini Space Invaders, and is thinking of completing the top-20 of his youth. Pacman, Asteroids, and Missile Command are next. We can’t wait.

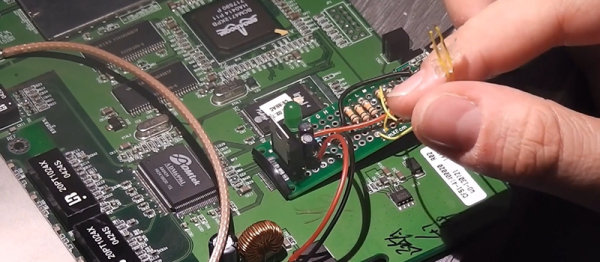

There are (ahem) a couple of Raspberry-Pi-powered video game emulators on Hackaday, so it’s a little awkward to pick one or two to link in. We’ll leave you with this build that also uses a small CRT monitor to good effect albeit in less-fancy clothing.