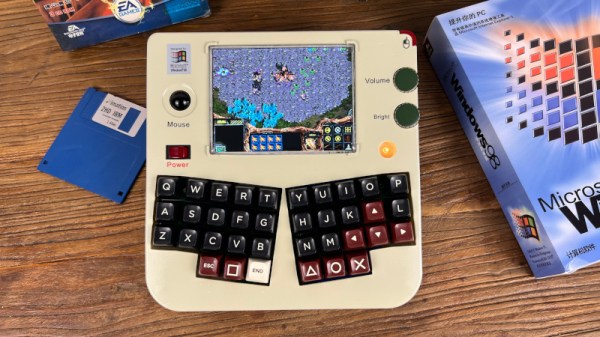

Handheld computers have become very much part of the hardware hacker scene, as the advent of single board computers long on processor power but short on power consumption has given us the tools we need to build them ourselves. Handheld retrocomputers face something of an uphill struggle though, as many of the components are over-sized, and use a lot of power. [Changliang Li] has taken on the task though, putting an industrial Pentium PC in a rather well-designed SLA printed case.

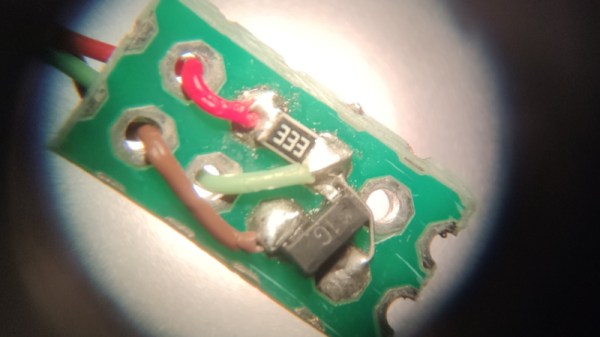

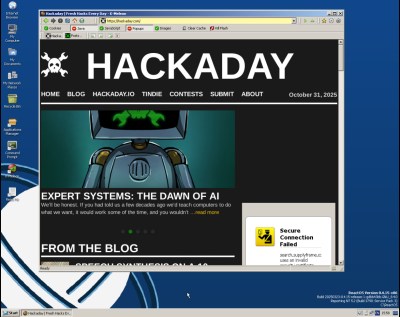

Aside from the motherboard there’s a VGA screen, a CompactFlash card attached to the IDE interface, and a Logitech trackball. As far as we can see the power comes from a USB-C PD board, and there’s a split mechanical keyboard on the top side. It runs Windows 98, and a selection of peak ’90s games are brought out to demonstrate.

We like this project for its beautiful case and effective use of parts, but we’re curious whether instead of the Pentium board it might have been worth finding a later industrial PC to give it a greater breadth of possibilities, there being few x86 SBCs. Either way it would have blown our minds back in ’98, and we can see it’s a ton of fun today. Take a look at the machine in the video below the break.