Many of us like a keyboard with a positive click noise when we type. You might want to rethink that, though, in light of a new paper from the UK that shows how researchers trained an AI to decode keystrokes from noise on conference calls.

The researchers point out that people don’t expect sound-based exploits. The paper reads, “For example, when typing a password, people will regularly hide their screen but will do little to obfuscate their keyboard’s sound.”

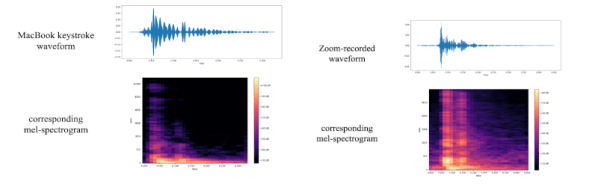

The technique uses the same kind of attention network that makes models like ChatGPT so powerful. It seems to work well, as the paper claims a 97% peak accuracy over both a telephone or Zoom. In addition, where the model was wrong, it tended to be close, identifying an adjacent keystroke instead of the correct one. This would be easy to correct for in software, or even in your brain as infrequent as it is. If you see the sentence “Paris im the s[ring,” you can probably figure out what was really typed.

We’ve seen this done before, but this technique raises the bar. As sophisticated as keyboard listening was back in the 1970s, you can only imagine what the three-letter agencies can do these days.

In the meantime, the mitigation for this particular threat seems obvious — just start screaming whenever you type in your password.