If you ever wanted to win a bar bet about a world record, you probably know about the Guinness book for World Records. Did you know, though, that there are some robots in that book? Guinness pointed some out in a recent post.

Ever wonder about the longest table-tennis rally with a robot or the fastest robotic cube solver? No need to wonder anymore.

Our favorite was the fastest robot to solve a puzzle cube. This robot solved the Rubik’s Cube in 103 milliseconds! Don’t blink or you’ll miss it in the video embedded. Of course, the real kudos go to the team that created the robot: [Matthew Patrohay], [Junpei Ota], [Aden Hurd], and [Alex Berta].

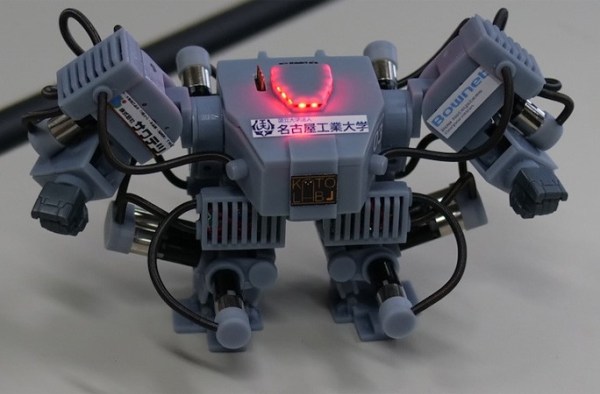

Another favorite was the smallest humanoid robot. In order to win this record, the robot must be able to move its shoulders, elbows, knees, and hips just like a human. It also has to be able to walk on two feet. This tiny little guy meets the requirements and stands only 57.6 mm (2.26 in) tall! Created by [Tatsuhiko Mitsuya] in April 2024, this robot can be controlled via Bluetooth.

We’ve seen entries in this category before — check them out in Almost Breaking The World Record For The Tiniest Humanoid Robot, But Not Quite.

Continue reading “Record-Breaking Robots At Guinness World Records”