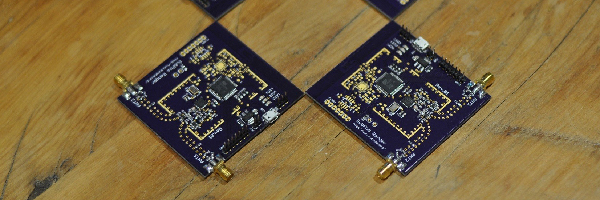

Get ready to rumble! [Thierry] made the exact same Hello-World-esque project with two microcontrollers (that are now technically produced by the same firm!) to see how the experience went.

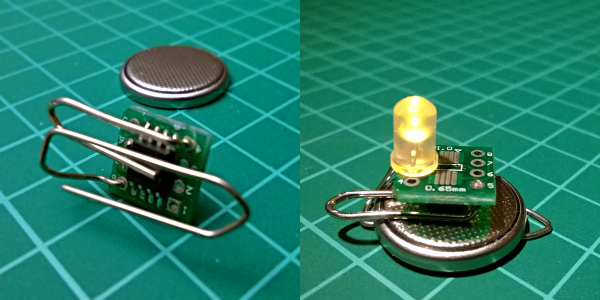

It’s not just an LED-blinker, though. He added in a light-detection function so that it only switches on at night. It uses the Forest Mims trick of reverse-biasing the LED and waiting for it to discharge its internal capacitance. The point is, however, that it gives the chip something to do instead of simply sleeping.

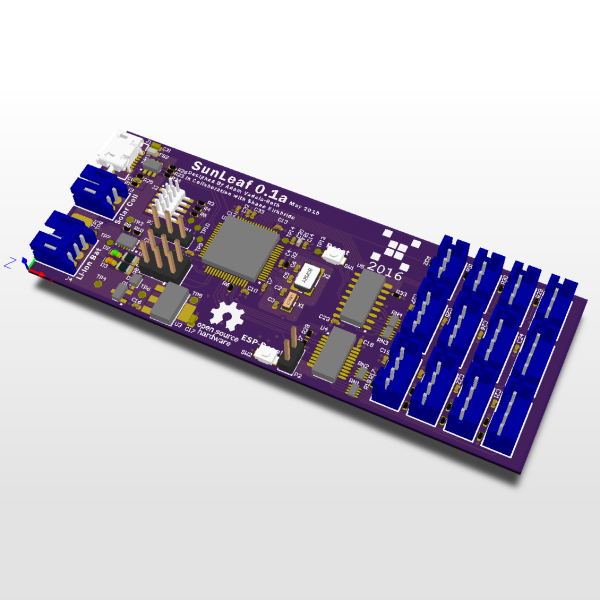

Although he’s an AVR user by habit, [Thierry] finds in favor of the PIC because it’s got a lower power draw both when idling and when awake and doing some computation. This is largely because the PIC has an onboard low-power oscillator that lets it limp along at 32 kHz, but also because the chip has a lower power consumption in general. In the end, it’s probably a 10% advantage to the PIC on power.

If you’re competent with one of the two chips, but not the other, his two versions of the same code would be a great way to start familiarizing yourself with the other. We really like his isDarkerThan() function which makes extensive use of sleep modes on both chips during the LED’s discharge period. And honestly, at this level the code for the two is more similar than different.

(Oh, and did you notice [Thierry]’s use of a paper clip as a coin-cell holder? It’s a hack!)

Surprisingly, we’ve managed to avoid taking a stray bullet from the crossfire that occasionally breaks out between the PIC and AVR fans. We have covered a “shootout” before, and PIC won that round too, although it was similarly close. Will the Microchip purchase of Atmel calm the flames? Let’s find out in the comment section. We have our popcorn ready!