In this week’s edition of, ‘why you should care that Behringer is cloning a bunch of vintage synths’, I present to you this amazing monstrosity. Yes, it’s a vertical video of a synthesizer without any sound. Never change, Reddit. A bit of explanation: this is four Behringer Model Ds (effectively clones of the Moog Minimoog, the Behringer version is called the ‘Boog’) stacked in a wooden case. They are connected to a MIDI keyboard ‘with Arduinos’ that split up the notes to each individual Boog. This is going to sound amazing and it’s one gigantic wall of twelve oscillators and it only cost $800 this is nuts.

Tuesday is Fastnacht day. Fill your face with fried dough.

The biggest news this week is the release of a ‘folding’ phone. This phone is expensive at about $3000 list, but keep in mind this is a flagship phone, one that defines fashion, and an obvious feature that will eventually be adopted by lower-cost models. Who knows what they’ll think of next.

It’s a new Project Binky! This time, we’re looking at cutting holes in the oil sump, patching those holes, cutting more holes in an oil sump, patching those holes, wiring up a dashcam, and putting in what is probably the third or fourth radiator so far.

Here’s a Kickstarter for new Nixie tubes. It’s a ZIN18, which I guess means an IN18, a tube with a 40mm tall set of numbers. This is the king of Nixie clocks, and one tube will run you about $100. Nah, you can also get new Nixies here.

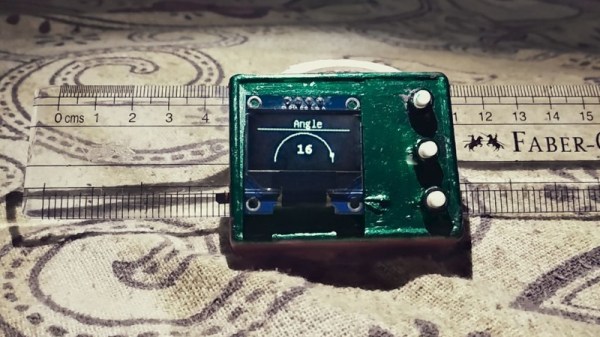

The Sipeed K210 is a RISC-V chip with built-in neural networks. Why should you care? Because it’s RISC-V. It’s also pretty fast, reportedly 5 times as fast as the ESP32. This is a 3D rendering test of the K210, with all the relevant code on the Github.

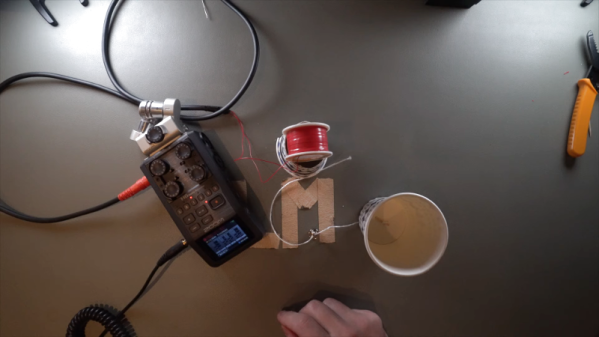

I’m not sure if everyone is aware of this, but here’s the best way to desolder through-hole parts. Heat the solder joint up and whack it against a table. It never fails. Hitting things is the best way to make them do what you want.