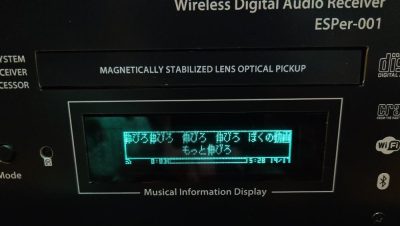

What do you get when you combine an ESP32, a 16-bit DAC, an antique VFD, and an IDE CD-ROM drive? Not much, unless you put in the work, which [Akasaka Ryuunosuke] did to create ESPer-CDP, a modern addition for your hi-fi rack.

It plays CDs (of course), but also can also scrobb the disks to Last.fm, automatically fetch track names and lyrics for CDs, and of course stream internet radio. It even acts as a Bluetooth speaker, because when you have an ESP32 and a DAC, why not? Of course we cannot help but award extra style points for the use of a VFD, a salvaged Futaba GP1232A02. There’s just something about VFDs and stereo equipment that makes them go together like milk and cookies.

In terms of CD access, it looks like the IDE interface is being used to issue ATAPI commands to the CD-ROM drive to get audio out via S/PDIF. (Do you remember when you had to hook your CD drive to your sound card to play music CDs?) This goes through a now-discontinued WM8805 receiver — a sign this project has been in the works for a while — that translates S/PDIF into an I2S stream the ESP32 can easily work with.

Work with it it does, with the aforementioned scrobbing, along with track ID and time-sinked lyrics via CDDB or MusicBrainz. The ESP32 should have the computing power to pull data through the IDE bus and decode it, but we have to admit that this hack gets the job done — albeit at the expense of losing the ability to read data CDs, like MP3 or MIDI. [Akasaka Ryuunosuk] has plans to include such functionality into v2, along with the ability to use a more modern SATA CD-ROM drive. We look forward to seeing it, especially if it keeps the VFD and classic styling. It just needs to be paired with a classic amplifier, and maybe a DIY turntable to top off the stack.

Thanks to [Akasaka Ryuunosuke] for the tip. If you also crave our eternal gratitude (which is worth its weight in gold, don’t forget), drop us a tip of your own. We’d love to hear from you.