When you’re a teenager new to the sensations of driving, it seems counterintuitive to “turn into the skid”, but once you’ve got a few winters of driving under your belt, you’re drifting like a pro. We learn by experience, and as it turns out, so does this fully autonomous power-sliding rally truck.

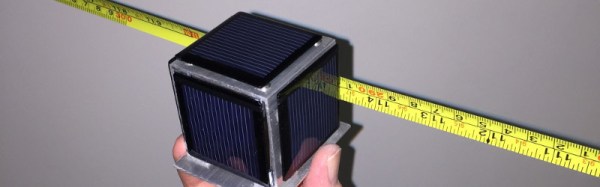

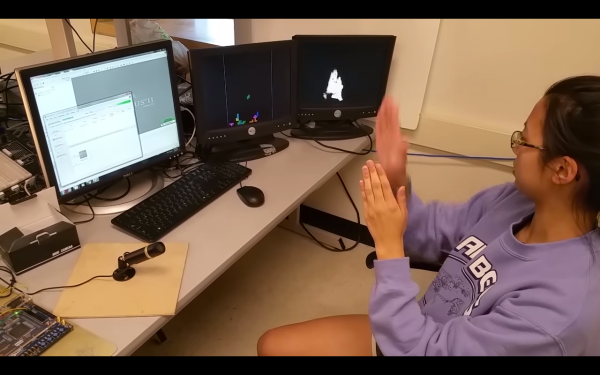

Figuring out how to handle friction-optional roadways is entirely the point of the AutoRally project at Georgia Tech, which puts a seriously teched-up 1/5 scale rally truck through its paces on an outdoor dirt track. Equipped with high-precision IMU, high-resolution GPS, dual front-facing cameras, and Hall-effect sensors on each wheel sampled at 70 Hz, the on-board Quad-core i7 knows exactly where the vehicle is and what the relationship between it and the track is at all times. There’s no external sensing or computing – everything needed to run the track is in the 21 kg truck. The video below shows how the truck navigates the oval track on its own with one simple goal – keep the target speed as close to 8 meters per second as possible. The truck handles the red Georgia clay like a boss, dealing not only with differing surface conditions but also with bright-to-dark lighting transitions. So far the truck only appears to handle an oval track, but our bet is that a more complex track is the next step for the platform.

While we really like the ride-on scale of this autonomous chase vehicle, other than that there haven’t been too many non-corporate self-driving vehicle hacks around here lately. Let’s hope that AutoRally is an indication that the hackers haven’t ceded the field to Google entirely. Why let them have all the fun?

Continue reading “Autonomous Truck Teaches Itself To Powerslide”