As part of his quest to find the best affordable generator for his DIY hydroelectric power system, [FarmCraft101] is trying out a range of off-the-shelf and DIY solutions, with in his most recent video trying his hands at the very relaxing activity of rewiring the stator of an alternator.

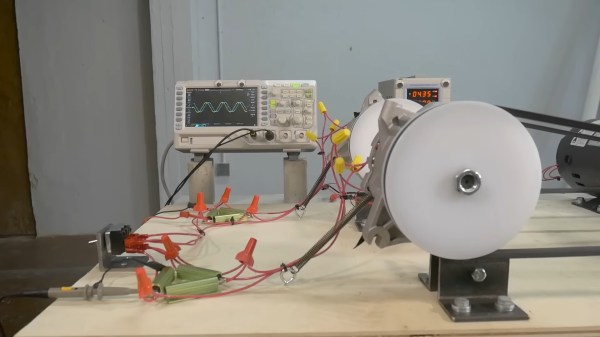

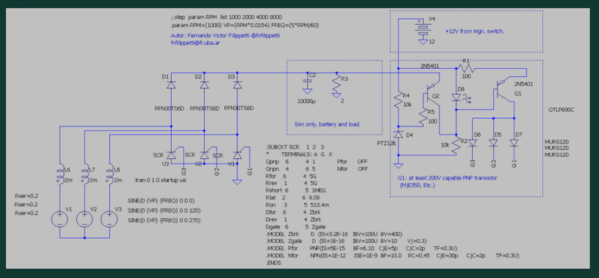

Normally car alternators output 12VDC after internal rectification, but due to the hundreds of meters from the turbine to the shed, he’d like a higher voltage to curb transmission losses. The easiest way to get a higher voltage out of a car alternator is to change up the wiring on the stator, which is definitely one of those highly educational tasks.

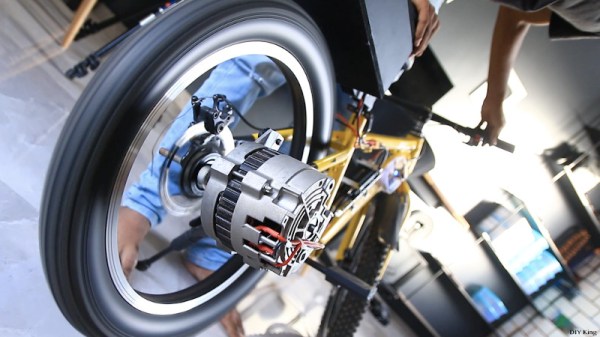

Disassembling an alternator is easy enough, but removing the copper windings from the stator is quite an ordeal, as they were not designed to ever move even a fraction of a millimeter after assembly.

With that arduous task finished, the rewinding was done using 22 AWG copper enamel wire, compared to the original 16 AWG wire, and increasing the loops per coil from 8 to 30. This rewinding isn’t too complicated if you know what you’re doing, with each coil on each of the three windings placed in an alternating fashion, matching the alternating South/North poles on the rotor.