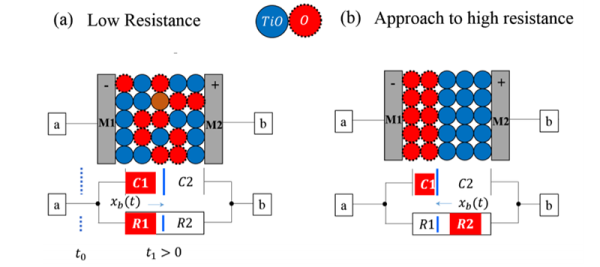

Fungi make up a massive, interconnected part of Earth’s ecosystems, yet they’re vastly underrepresented in research and public consciousness compared to plants and animals. That may change in the future though, as a group of researchers at The Ohio State University have found a way to use fungi as organic memristors — hinting at a possible future where fungal networks help power our computing devices.

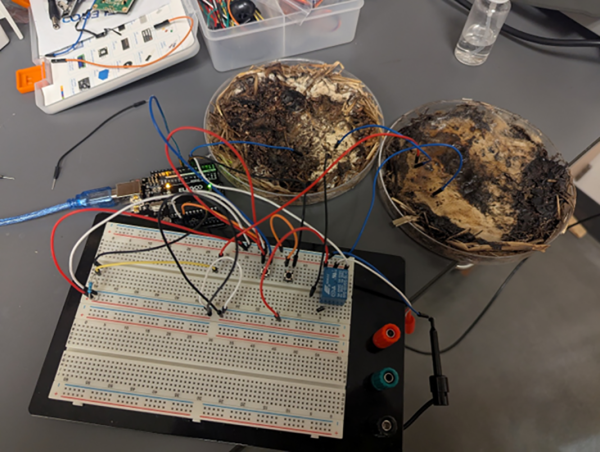

A memristor is a passive electronic component whose resistance changes based on the voltage and current that has passed through it, which means it can effectively remember past electrical states even when power is removed. To create these circuit components with fungus, the researchers grew shiitake and button mushroom mycelium for these tests, dehydrated their samples for a number of days, and then attached electrodes to the samples. After misting them briefly to restore conductivity, the samples were exposed to various electrical wave forms at a range of voltages to determine how effective they were at performing the duties of a memristor. At one volt these systems were the most consistent, and they were even programmed to act like RAM where they achieved a frequency of almost 6 kHz and an accuracy of 90%.

In their paper, the research group notes a number of advantages to building fungal-based components like these, namely that they are much more environmentally friendly and don’t require the rare earth metals that typical circuit components do. They’re also easier to grow than other types of neural organoids, require less power, weigh less, and shiitake specifically is notable for its radiation resistance as well. Some work needs to be done to decrease the size required, and with time perhaps we’ll see more fungi-based electrical components like these.