DIY 3D printing in metal is a lot more complicated than we thought. And this video from [Metal Matters] shows two approaches, many many false starts, and finally, a glorious 78.9% success! (And it’s embedded below for your enjoyment.)

The first half of the video is dedicated to the work on a laser welding system that doesn’t pan out in the end at all. But the missteps are worth watching as well, and they hammer home the difficulties of melting metal reliably with nothing more than coherent light. Things like reflection, the difficulty of getting good process control cameras, and finally the whole thing slumping as multiple layers stack up on each other make this approach to 3D construction look nearly impossible.

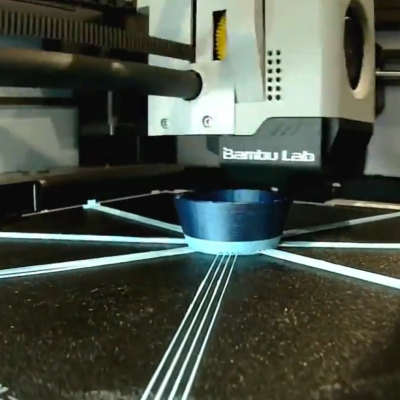

Indeed, around halfway through the video, the focus shifts toward a metal-powder sintering machine, and this one is a success! Metal dust is deposited layer by layer, and fused with a totally different laser. The tricky bits here range from esoteric problems like making the laser fuse the metal dust without blasting it, to simple things like the geometry of the scraper that ensures even layer heights. And once you’ve got all that down, getting a good pattern down for 2D infill in metal is non-trivial.

A sweet half-scale metal Benchy emerges at the end, so why does [Metal Matters] call this a 78.9% success? Because that’s the density of the final print, and he is shooting for 100%. But we wouldn’t be so harsh. We’ve seen how far he’s come since the first machines, and this is a huge advance. We’re looking forward to the next video update in a year or two!

Continue reading “First Benchies In Stainless Steel, With Lasers”