Often, the only liquid level indicator you need is your eyes, such as when looking at your cold beverage on a summer’s day. Other times, though, it’s useful to have some kind of indicator light that can tell you the same. [Hulk] shows us how to build one for a water tank using a single IC and some cheap supporting components.

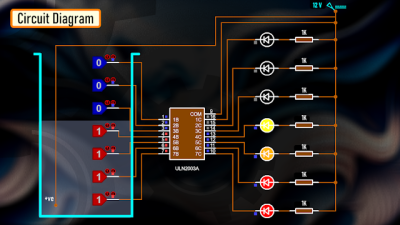

If you’re unfamiliar with the ULN2003, it’s a simple Darlington transistor array with seven transistors inside. It can thus be used to switch seven LEDs without a lot of trouble. In this case, green, yellow, and red LEDs were hooked up to the outputs of the transistors in the ULN2003. Meanwhile, the base of each transistor is connected to an electrode placed at a different height in the water tank. A further positive electrode is placed in the tank connected to 12 volts. As the water raises to the height of each electrode, current flow from the base to the positive electrode switches the corresponding transistor on, and the LED in turn. Thus, you have a useful liquid level indicator with seven distinct output levels.

If you’re unfamiliar with the ULN2003, it’s a simple Darlington transistor array with seven transistors inside. It can thus be used to switch seven LEDs without a lot of trouble. In this case, green, yellow, and red LEDs were hooked up to the outputs of the transistors in the ULN2003. Meanwhile, the base of each transistor is connected to an electrode placed at a different height in the water tank. A further positive electrode is placed in the tank connected to 12 volts. As the water raises to the height of each electrode, current flow from the base to the positive electrode switches the corresponding transistor on, and the LED in turn. Thus, you have a useful liquid level indicator with seven distinct output levels.

It’s a neat build that might prove useful if you need to check levels in a big opaque tank at a glance. Just note that it might need some maintenance over time, as the electrodes are unlikely to remain completely corrosion free if left in water. We’ve seen some other great uses of the ULN2003 before, too. Video after the break.

Continue reading “A Simple Liquid Level Indicator With A Single IC”