Some time ago, while designing the PCB for the Sony Vaio replacement motherboard, I went on a quest to find a perfect 5 V boost regulator. Requirements are simple – output 5 V at about 2A , with input ranging from 3 V to 5 V, and when the input is 5 V, go into “100% duty” (“pass-through”/”bypass”) mode where the output is directly powered from the input, saving me from any conversion inefficiencies for USB port power when a charger is connected. Plus, a single EN pin, no digital configuration, small footprint, no BGA, no unsolicited services or offers – what more could one ask for.

As usual, I go to an online shop, set the parameters: single channel, all topologies that say “boost” in the name, output range, sort by price, download datasheets one by one and see what kind of nice chips I can find. Eventually, I found the holy grail chip for me, the MIC2876, originally from Micrel, now made by Microchip.

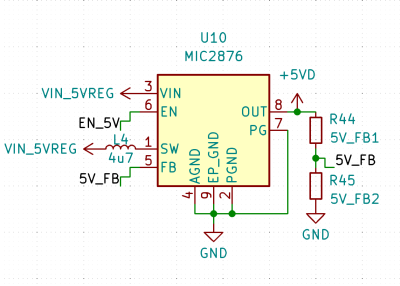

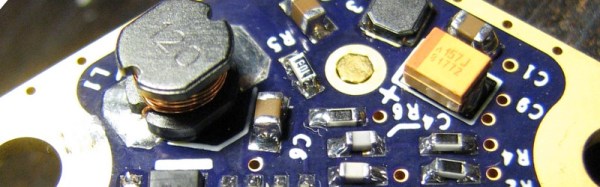

MIC2876 is a 5 V regulator with the exact features I describe above – to a T! It also comes with cool features, like a PG “Power good” output, bidirectional load disconnect (voltage applied to output won’t leak into input), EMI reduction and efficiency modes, and it’s decently cheap. I put it on the Sony Vaio board among five other regulators, ordered the board, assembled it, powered it up, and applied a positive logic level onto the regulator’s EN pin.

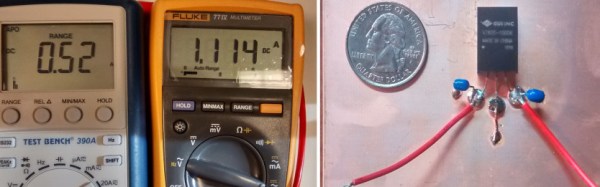

Immediately, I saw the regulator producing 3 V output accompanied by loud buzzing noise – as opposed to producing 5 V output without any audible noise. Here’s how the regulator ended up failing, how exactly I screwed up the design, and how I’m creating a mod board to fix it – so that the boards I meticulously assembled, don’t go to waste.

Some Background… Noise

Continue reading “Switching Regulators: Mistake Fixing For Dummies”