With many words which are commonly used in everyday vocabulary, we are certain that we have a solid grasp of what they do and do not mean, but is this really true? Take the word ‘robot’ for example, which is more commonly used wrongly rather than correctly when going by the definition of the person who coined it: [Karel Čapek]. It was the year 1920 when his play Rossumovi Univerzální Roboti was introduced to the world, which soon saw itself translated and performed around the world, with the English-speaking world knowing it as R.U.R.: Rossum’s Universal Robots.

Up till then, the concept of a relatively self-operating machine was known as an automaton, as introduced by the Ancient Greeks, with the term ‘android’ being introduced as early as the 18th century to mean automatons that have a human-like appearance, but are still mechanical contraptions. When [Čapek] wrote his play, he did not intend to have non-human characters that were like these androids, but rather pure artificial life: biochemical systems much like humans, using similar biochemical principles as proteins, enzymes, hormones and vitamins, assembled from organic matter like humans. These non-human characters he called ‘roboti’, from Old Czech ‘robot’ (robota: “drudgery, servitude”), who looked human, but lacked a ‘soul’.

Despite this intent, the run-away success of R.U.R. led to anything android- and automaton-like being referred to as a ‘robot’, which he lamented in a 1935 column in Lidové Noviny. Rather than whirring and clunking pieces of machinery being called ‘automatons’ and ‘androids’ as they had been for hundreds of years, now his vision of artificial life had effectively been wiped out. Despite this, to this day we can still see the traces of the proper terms, for example when we talk about ‘automation’, which is where automatons (‘industrial robots’) come into play, like the industrial looms and kin that heralded the Industrial Revolution.

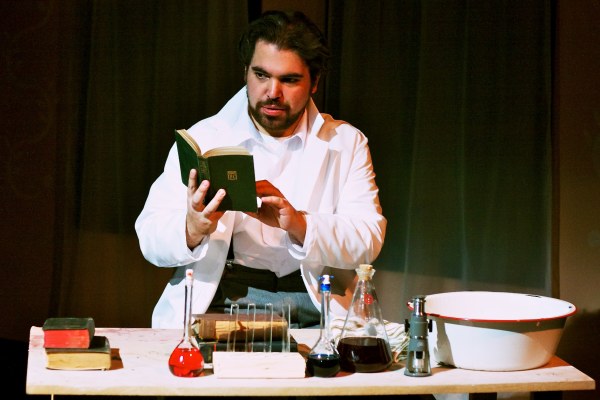

(Heading image: Performance of R.U.R. by Flat Earth Theatre, showing the mixing of robot ingredients)