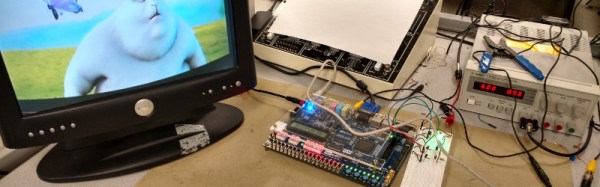

The student projects that come out of [Bruce Land]’s microcontroller- and FPGA-programming classes feature here a lot, simple because some of them are amazing, but also because each project is a building-block for another. And we hope they will be for you.

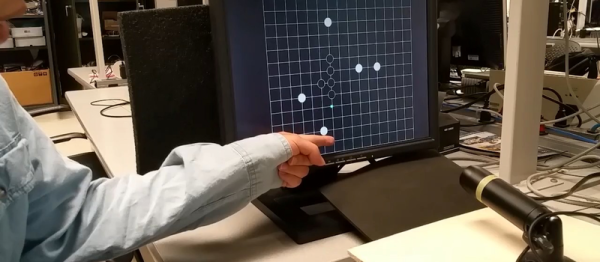

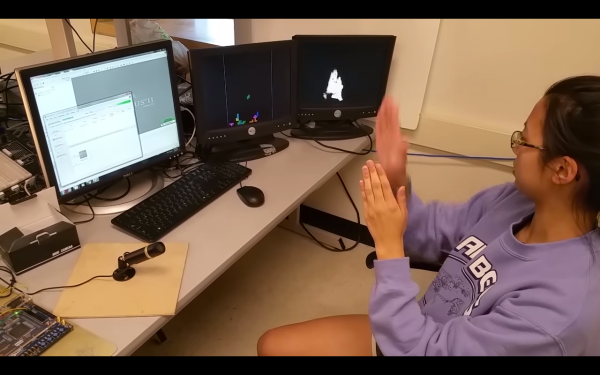

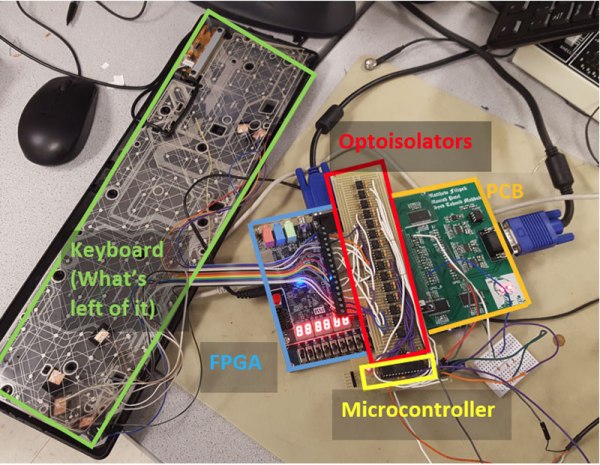

This time around, [Junyin Chen] and [Ziqi Yang] created a five-in-a-row video game that is controlled by a pointing finger. A camera, pointed at the screen, films the player’s hand and passes the VGA data to an FPGA. And that’s where things get interesting.

An algorithm in the FPGA detects skin color and, after a few opening and closing operations, comes up with a pretty good outline of the hand. The fingertip localization is pretty clever. They sum up the number of detected pixels in the X- and Y-axis, and since a point finger is long and thin, locate the tip because it’s going to have a maximum value in one axis and a minimum along the other. Sweet (although the player has to wear long sleeves to make it work perfectly).

How does the camera not pick up the game going on in the background? They use a black-and-white game field that the skin-color detection simply ignores. And the game itself runs in a Nios embedded processor in the FPGA. There’s a lot more detail on the project page, and of course there’s a demo video below.

We love to follow along with Prof. Land‘s classes. His video series is invaluable, and the course projects have been an inspiration.