Retro gaming consoles exploded with the introduction of the Raspberry Pi and other similar single-board Linux computers. They all work the same way in that they emulate the original game console hardware with software. The game ROM is then dumped to a file and will play like the original. While this works just fine for the vast majority of us who want to get a dose of nostalgia as we chase the magic 1-up mushroom, gaming purists are not satisfied. They can tell the subtle differences between emulation and real hardware. And this is where our story begins.

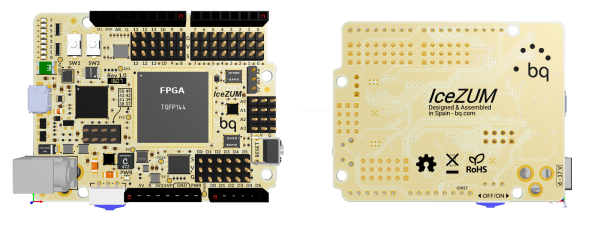

Meet the Coleco Chameleon. What appears to be just another run-of-the-mill retro gaming console is not what you think. It has an FPGA core that replicates the actual hardware, to the delight of hardcore retro game  enthusiasts around the world. To get it to the masses, they started an ambitious 2 million US dollar Indiegogo campaign, which has unfortunately come to a screeching halt.

enthusiasts around the world. To get it to the masses, they started an ambitious 2 million US dollar Indiegogo campaign, which has unfortunately come to a screeching halt.

Take a close look at the header image. That blue circuit board in there is nothing but an old PCI TV tuning card. To make matters worse, it also appears that their prototype system which was displayed at the Toy Fair in New York was just the guts of an SNES Jr stuffed into their shell.

This scam is clearly busted. However, the idea of reconstructing old gaming console hardware in an FPGA is a viable proposition, and there is demand for such a device from gaming enthusiasts. We can only hope that the owners of the Coleco Chameleon Kickstarter campaign meant well and slipped up trying to meet demand. If they can make a real piece of hardware, it would be welcomed.