For Christmas, [Lior] received a Baofeng UV5R radio. He didn’t have an amateur radio license, so he decided to use it as a police scanner. Since the schematics were available, he cracked it open and hacked it.

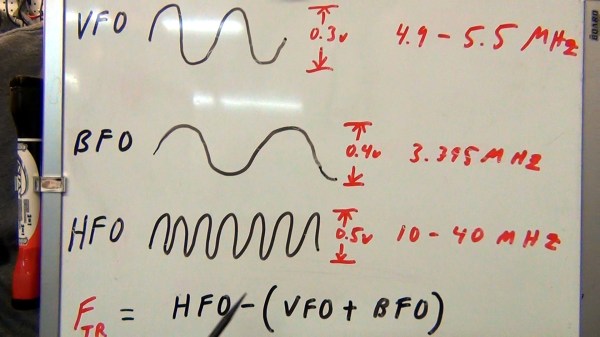

This $40 radio communicates on the 136-174 MHz and 400-480 MHz bands. It uses a one-time programmable microcontroller and the RDA1846 transceiver. With the power traces to the MCU cut, [Lior] was able to send his own signals to the chip over I2C using an Arduino. He also recorded the signals sent by the stock microcontroller during startup, so that he could emulate it with the Arduino.

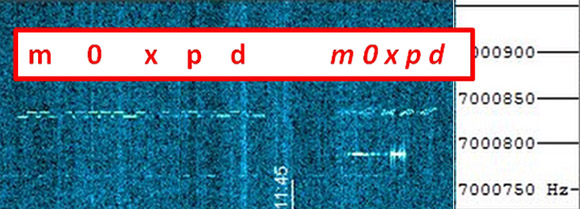

Once communication was working on an Arduino, [Lior] decided to get rid of the stock microcontroller. He desoldered the chip, leaving exposed pads to solder wires to. Hooking these up to the Arduino gave him a programmable way to control the device. He got his radio license and implemented transmission of Morse Code, and an Arduino sketch is available in the write up.

[Lior] points out that his next step is to make a PCB to connect a different microcontroller to the device. This will give him a $40 radio that is fully programmable. After the break, check out a video of the hacked radio in action.