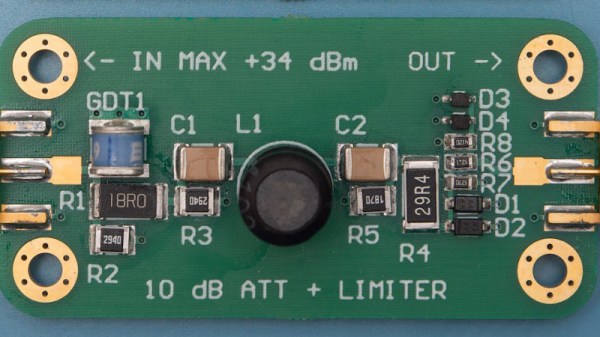

The HP 11947A is something of a footnote in the back catalogue of Hewlett Packard test equipment. An attenuator and limiter with a bandwidth in the megahertz rather than the gigahertz. It’s possible that few laboratories have much use for one in 2019, but it does have one useful property: a full set of schematics and technical documentation. [James Wilson] chose the device as the subject of a clone using surface mount devices.

The result is very satisfyingly within spec, and he’s run a battery of tests to prove it. As he says, the HP design is a good one to start with. As a device containing only passive components and with a maximum frequency in the VHF range this is a project that makes a very good design exercise for anyone interested in RF work or even who wishes to learn a bit of RF layout. At these frequencies there are still a significant number of layout factors that can affect performance, but the effect of conductor length and stray capacitance is less than the much higher frequencies typically used by wireless-enabled microcontrollers.