Remember subliminal advertising? The idea was that a movie theater operator would splice a single frame showing a bucket of hot buttered popcorn into a movie, which moviegoers would see and process on a subconcious level and rush to the concession stand to buy the tub o’ petrochemical-glazed starch they suddenly craved. It may or may not work on humans, but it appears to work on cars with advanced driver assistance, which can be spoofed by “phantom street signs” flashed on electronic billboards. Security researchers at Ben Gurion University stuck an image of a stop sign into a McDonald’s ad displayed on a large LCD screen by the side of the road. That was enough to convince a Tesla Model X to put on the brakes as it passed by the sign. The phantom images were on the screen anywhere from an eighth of a second to a quarter second, so these aren’t exactly subliminal messages, but it’s still an interesting attack that bears looking into. And while we’re skeptical about the whole subliminal advertising thing in the first place, for some reason we really want a bacon cheeseburger right now.

Score one for the good guys in the battle against patent trolls. Mycroft AI, makers of open-source voice assistants, proudly announced their latest victory against what they claim are patent trolls. This appears to be one of those deals where a bunch of investors get together and buy random patents, and then claim that a company that actually built something infringes on their intellectual property. Mycroft got a letter from one such entity and decided to fight it; they’ve won two battles so far against the alleged trolls and it looks pretty good going forward. They’re not pulling their punches, either, since Mycroft is planning to go after the other parties for legal expenses and punitive damages under the State of Missouri’s patent troll legislation. Here’s hoping this sends a message to IP squatters that it may not be worth the effort and that their time and money are better spent actually creating useful things.

Good news from Mars — The Mole is finally completely buried! We’ve been following the saga of the HP³, or “Heat Flow and Physical Properties Package” aboard NASA’s Mars InSight lander for quite a while. The self-drilling “Mole”, which is essentially the guts of an impact screwdriver inside a streamlined case, has been having trouble dealing with the Martian regolith, which is simultaneously too soft to offer the friction needed to keep the penetrator in its hole, but also too hard to pierce in places where there is a “duricrust” of chemically amalgamated material below the surface. It took a lot of delicate maneuvers with the lander’s robotic arm to get the Mole back on track, and it’s clearly not out of the woods yet — it needs to get down to three meters depth or so to do the full program of science it was designed for.

If watching Martian soil experiments proceed doesn’t scratch your itch for space science, why not try running your own radio astronomy experiments? Sure, you could build your own radio telescope to do that, but you don’t even have to go that far — just log into PICTOR, the free-to-use radio telescope. It’s a 3.2-m parabolic dish antenna located near Athens, Greece that’s geared toward hydrogen line measurements of the galaxy. You can set up an observation run and have the results mailed back to you for later analysis.

Here’s a fun, quick hack for anyone who hates the constant drone of white noise coming from fans. Build Comics apparently numbers themselves among that crowd, and decided to rig up a switch to turn on their fume extractor only when the soldering iron is removed from its holder. This hack was executed on a classic old Weller soldering station, but could easily be adapted to Hakko or other irons

And finally, if you’ve never listened to a Nobel laureate give a lecture, here’s your chance. Andrea Ghez, co-winner of the 2020 Nobel Prize in physics for her work on supermassive black holes, will be giving the annual Maria Goeppert Mayer lecture at the University of Chicago. She’ll be talking about exactly what she won the Nobel for: “The Monster at the Heart of Our Galaxy”, the supermassive black hole Sagittarius A*. We suspect the talk was booked before the Nobel announcement, so in normal times the room would likely be packed. But one advantage to the age of social distancing is that everything is online, so you can tune into a livestream of the lecture on October 22.

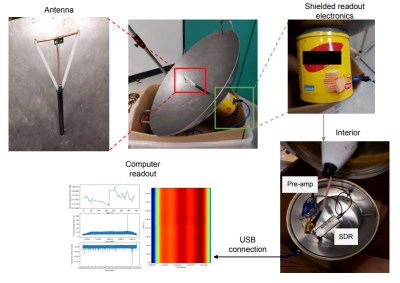

As for the signal processing chain, WTH holds few surprises. A Nooelec Sawbird+ H1 acts as preamp and filter for the 1420-MHz hydrogen line signal, which feeds into an RTL-SDR dongle. Careful attention is paid to proper grounding and shielding to keep the noise floor as low as possible. Mounting the antenna is a decidedly ad hoc affair, and aiming is as simple as eyeballing various stars near the center of the galactic plane — no need to complicate things.

As for the signal processing chain, WTH holds few surprises. A Nooelec Sawbird+ H1 acts as preamp and filter for the 1420-MHz hydrogen line signal, which feeds into an RTL-SDR dongle. Careful attention is paid to proper grounding and shielding to keep the noise floor as low as possible. Mounting the antenna is a decidedly ad hoc affair, and aiming is as simple as eyeballing various stars near the center of the galactic plane — no need to complicate things.

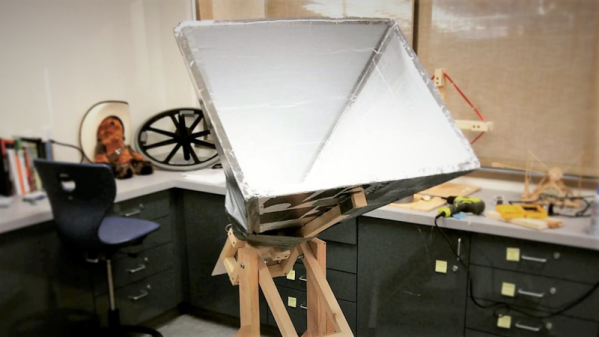

But to do any of this, you need a receiver, and that starts with a horn antenna to collect the weak signal. In collaboration with a former student, high school teacher [ArtichokeHeartAttack] built a pyramidal horn antenna of insulation board and foil tape. This collects RF signals and directs them to the waveguide, built from a rectangular paint thinner can with a quarter-wavelength stub antenna protruding into it. The signal from the antenna is then piped into an inexpensive

But to do any of this, you need a receiver, and that starts with a horn antenna to collect the weak signal. In collaboration with a former student, high school teacher [ArtichokeHeartAttack] built a pyramidal horn antenna of insulation board and foil tape. This collects RF signals and directs them to the waveguide, built from a rectangular paint thinner can with a quarter-wavelength stub antenna protruding into it. The signal from the antenna is then piped into an inexpensive