If you’ve ever dealt with a buggy Internet connection, you know how frustrating it can be. This project takes the guesswork out of mashing F5 over and over, or simply walking over to your router and ‘turning it on and off again.’

Necessity is the mother of invention, and when the folks at the Bitlair hackerspace in Amersfoort, Netherlands got tired of opening up a terminal to see if their network connection was down at this weekend’s Haxogreen camp they did what any self-respecting hackerspace would do: make a traffic light monitor the Internet.

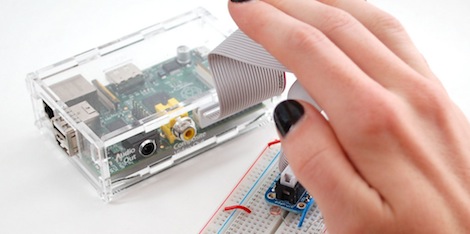

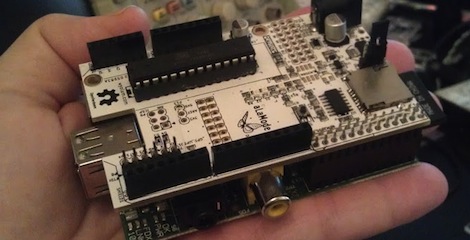

The traffic light is controlled by a Raspberry Pi the Bitlair folks had lying around attached to a spare traffic light they somehow obtained with a relay. Green means the Raspi can reach 8.8.8.8, red means there is no connection, and flashing lights means there is packet loss.

Not bad for a project put together in a few hours. Now if we only knew how they obtained a traffic light, ‘just lying around.’

Video after the break.

Continue reading “Checking Network Status With A Traffic Light”