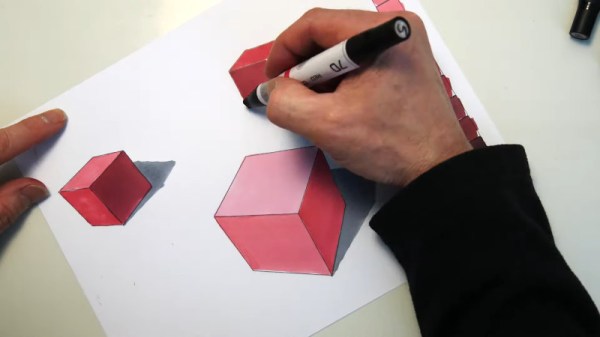

When doing high-end industrial illustration work, smooth gradients add a lot of production value to the final product. However, markers designed to do this well can be difficult to lay your hands on. [Eric] decided to create his own set of custom gradient markers, using commonly available supplies.

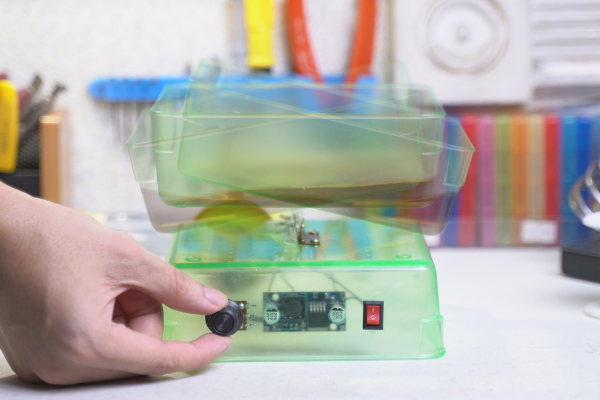

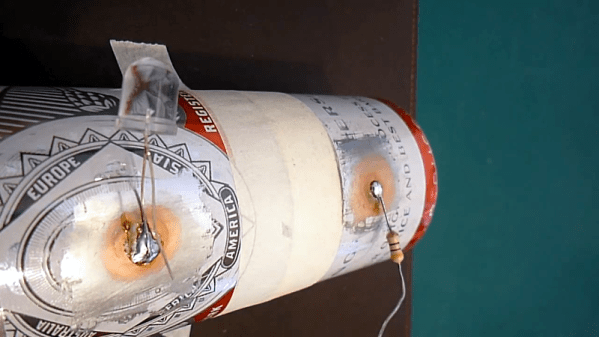

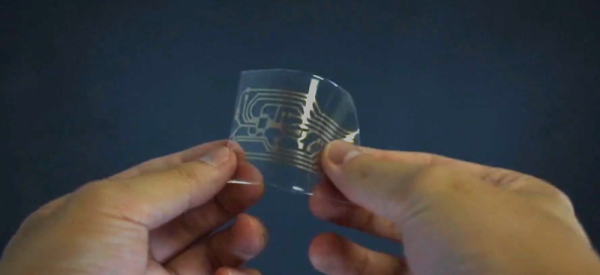

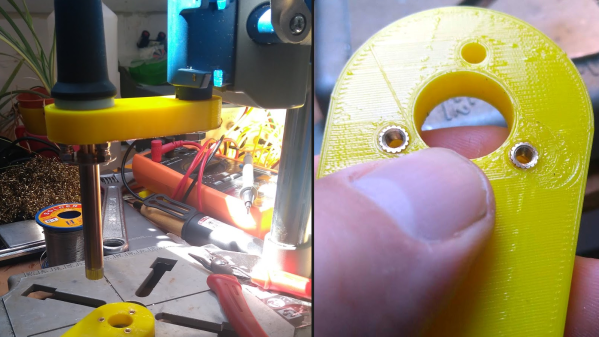

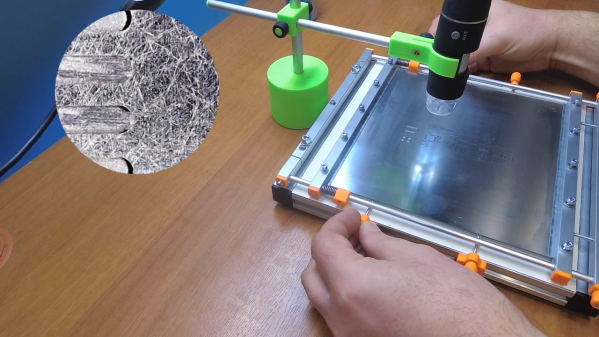

Starting with some existing markers that have dried out, the fabric ink reservoir inside is removed. A new one is created using tampons wrapped in heat-shrink, to replicate the construction of the original. Alcohol-based ink is required for smooth gradients, and [Eric] suggests using a heat gun to harvest the ink from a ballpoint pen, if store-bought is not available. The ink is then mixed with denatured alcohol to dilute it and injected into the fabric reservoir using a syringe. Each marker gets a slightly different ink mix to hit a range of lightness values for making smooth gradients.

It’s a tidy way of creating your own gradient markers in whatever color you may find useful. As a plus, the materials to do so are cheap and easy to obtain. We could even imagine 3D-printed marker bodies being an option, though nibs might prove a touch more difficult. We’ve seen [Eric]’s work before too, like this well-illustrated guide to using cardboard in product design. Video after the break.