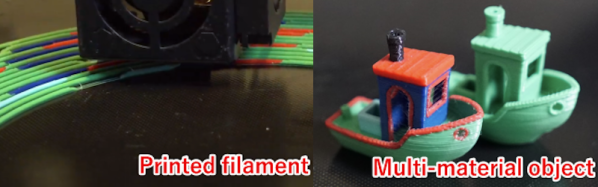

It’s an age-old problem. You draw up a nice 6.5-meter long motorboat and then discover the shape won’t allow for a fiberglass mold. What do you do? If you’re [Moi], you grab a few Kuka robots and 3D print it using thermoplastic with embedded glass fibers. A UV light cures the plastic and you wind up with printed fiberglass. That’s the story behind the MAMBO, a 3D printed powerboat.

Despite the color, the fiberglass isn’t blue out of the gate — the boat is painted. Still, it looks nice with lines inspired by [Sonny Levi]’s Arcidiavolo design from 1973. MAMBO stands for Motor Additive Manufacturing BOat. It has a dry weight of about 800 kg and is fitted with a cork floor, white leather seats, and an engine. We presume none of those things were 3D printed.

Despite the color, the fiberglass isn’t blue out of the gate — the boat is painted. Still, it looks nice with lines inspired by [Sonny Levi]’s Arcidiavolo design from 1973. MAMBO stands for Motor Additive Manufacturing BOat. It has a dry weight of about 800 kg and is fitted with a cork floor, white leather seats, and an engine. We presume none of those things were 3D printed.

Although it wasn’t fiberglass, we’ve seen a 3D printed boat before. In particular, the University of Maine’s giant 22,000 square foot printer cranked one out. We’ve also seen boats printed in standard PLA filament, which then had fiberglass cloth and resin applied after printing. True that one was only RC, but there’s no reason the concept couldn’t be scaled up if you had the patience.