Ham radio operators love to push the boundaries of their equipment. A new ham may start out by making a local contact three miles away on the 2m band, then talk to somebody a few hundred miles away on 20m. Before long, they may find themselves chatting to fellow operators 12,000 miles away on 160m. Some of the adventurous return to 2m and try to carry out long-distance conversations by bouncing signals off of the Moon, waiting for the signal to travel 480,000 miles before returning to Earth. And then some take it several steps further when they listen to signals from spacecraft 9.4 million miles away.

That’s exactly what [David Prutchi] set out to do when he started building a system to listen to the Deep Space Network (DSN) last year. The DSN is NASA’s worldwide antenna system, designed to relay signals to and from spacecraft that have strayed far from home. The system communicates with tons of inanimate explorers Earth has sent out over the years, including Voyager 1 & 2, Juno, and the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. Because the craft are transmitting weak signals over a great distance (Voyager 1 is 14 billion miles away!), the earth-based antennas need to be big. Real big. Each of the DSN’s three international facilities houses several massive dishes designed to capture these whispers from beyond the atmosphere — and yet, [David] was able to receive signals in his back yard.

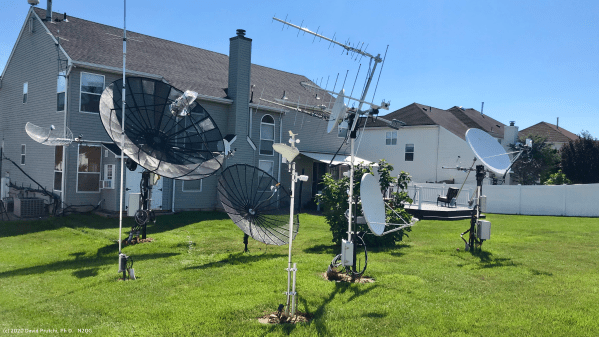

Sporting a stunning X-band antenna array, a whole bunch of feedlines, and some tracking software, he’s managed to eavesdrop on a handful of spacecraft phoning home via the DSN. He heard the first, Bepi-Colombo, in May 2020, and has only improved his system since then. Next up, he hopes to find Juno, and decode the signals he receives to actually look at the data that’s being sent back from space.

We’ve seen a small group of enthusiasts listen in on the DSN before, but [David]’s excellent documentation should provide a fantastic starting point for anybody else interested in doing some interstellar snooping.