The key to Short Takeoff and Landing (STOL) operations is the ability to fly slow– really slow. That’s how you get up fast without a long takeoff roll to build up speed. Usually, this involves layers of large flaps and/or leading edge slats, but [rctestflight] on YouTube decided he wanted to take a more active approach with a fully blown wing.

The airplane in question is R/C, of course, and good thing: these wings would be a safety nightmare for a manned aircraft. With a blown wing, air is blown out of a slot on the top end of the wing, producing a high-speed, high-pressure zone that keeps the wing flying when it would otherwise be completely stalled out. As long as everything works, that’s great! If an engine fails, well, suddenly you aren’t flying anymore — and you’re going too slow to glide. It ends badly.

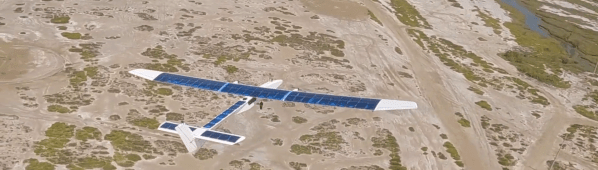

[rctestflight] doesn’t have to worry about that, though, because this foamboard and pink styro R/C aircraft carries nothing that can’t survive a crash. (A couple of electric ducted fans (EDCs), an Ardupilot, a radio, and a battery are all pretty shock-resistant.) The EDCs sit midway down the chord of the wings, and blow air into a plenum carved into the foam. On each wing, the exhaust from the fans is driven rearward from a slot created by a piece of carbon fiber. This air serves not only as a lift-enhancement but also as the plane’s sole propulsion and a component of its control system.

Continue reading “This Plane Flies Slow Because Its Wings Really Blow”