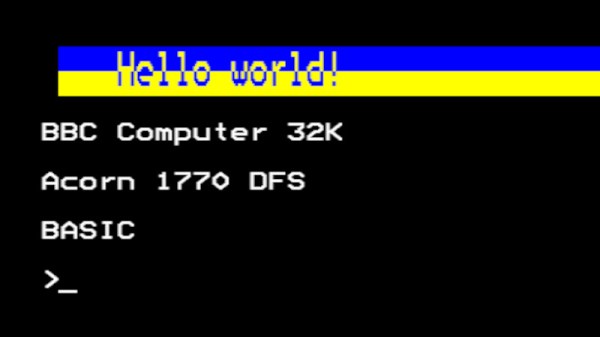

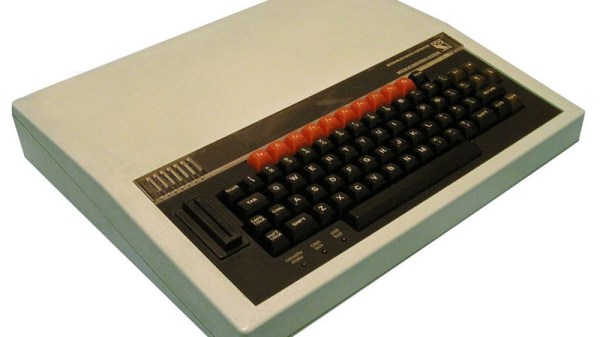

The BBC has a long history of teaching the world about computers. The broadcaster’s name was proudly displayed on the BBC Micro, and BBC Basic was the programming language developed especially for that computer. Now, BBC Basic is back and running on a whole mess of modern platforms.

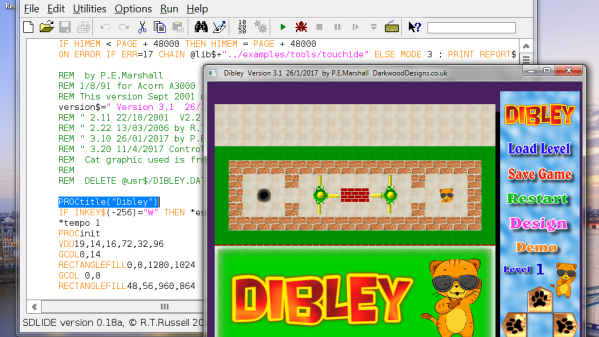

BBC Basic for SDL 2.0 will run on Windows, MacOS, x86 Linux, and even Raspberry Pi OS, Android, and iOS. Desktop versions of the programming environment feature a BASIC editor that has syntax coloring for ease of use, along with luxury features like search and replace that weren’t always available at the dawn of the microcomputer era. Meanwhile, the smartphone versions feature a simplified interface designed to work better in a touchscreen environment.

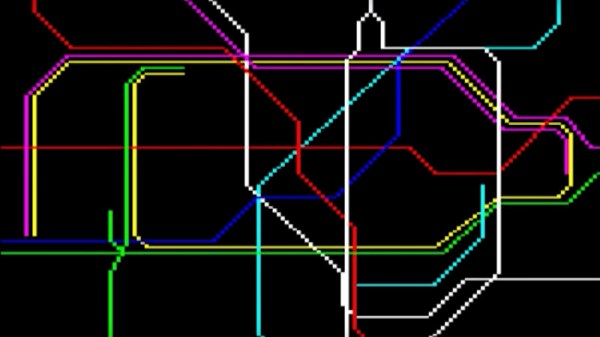

It’s weird to see, but BBC Basic can actually do some interesting stuff given the power of modern hardware. It can address up to 256 MB of memory, and work with far more advanced graphical assets than would ever have been possible on the original BBC Micro. If you honed your programming skills on that old metal, you might be impressed with what they can achieve with BBC Basic in a new, more powerful context.

If you’re passionate about the BBC and its history with computers, we’ve talked plenty about the BBC Micro in the past, too.

[Thanks to Stephen Walters for the tip!]