In the 2020s we’re used to software being readily accessible, and often free, whether as-in-beer or as-in-speech. This situation is a surprisingly new one, and in an earlier era of consumer software it was most often an expensive purchase. An anti-piracy industry sprang up as manufacturers tried to protect their products, and it’s one of those companies that [GloriousCow] examines in detail, following their trajectory from an initial success through to an ignominious failure driven by an anti-piracy tech too extreme even for the software industry.

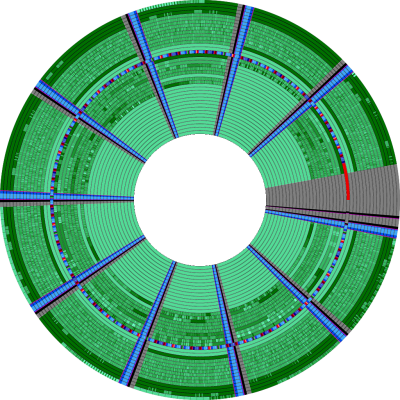

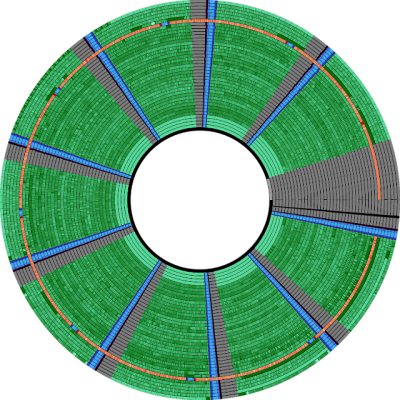

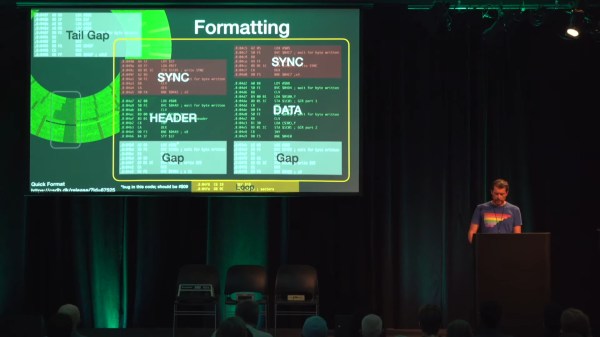

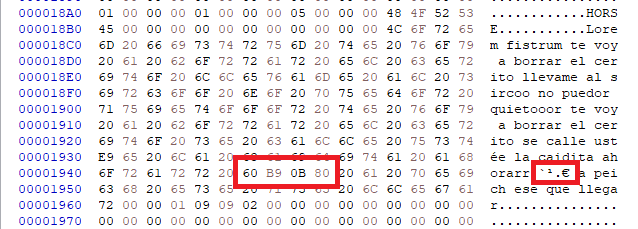

Vault Corporation made a splash in the marketplace with Prolok, a copy protection system for floppies that worked by creating a physically damaged area of the disc which wouldn’t be present on a regular floppy. The write-up goes into detail about the workings of the system, including how to circumvent a Prolok protected title if you find one. This last procedure resulted in a lawsuit between Prolok and Quaid Software, one of the developers of circumvention tools, which established the right of Americans to make backup copies of their owned software.

The downfall of Vault Corporation came with their disastrously misjudged Prolok Plus product, which promised to implant a worm on the hard disks of pirates and delete all their files in an act of punishment. Sensing the huge reputational damage of being tied to such a product the customers stayed away, and the company drifted into obscurity.

For those interested further in the world of copy protection from this era, we’ve previously covered the similar deep dives that [GloriousCow] has done on Softguard’s Superlok as well as the Interlock system from Electronic Arts.