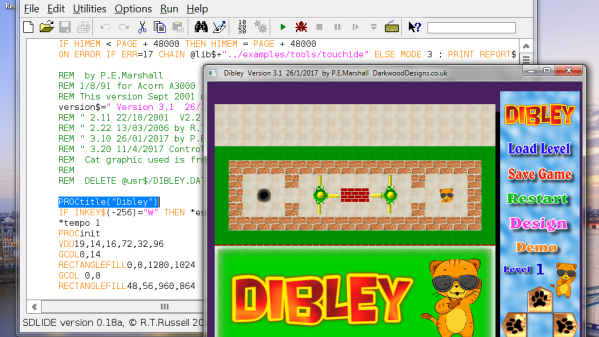

The BBC wanted to show everyone how a computer might be used in schools. A program aired in 1979 asks, “Will Computers Revolutionise Education?” There’s vintage hardware and an appearance of PILOT, made for computer instructions.

Using PILOT looks suspiciously like working with a modern chatbot without as much AI noise. The French teacher in the video likes that schoolboys were practicing their French verb conjugation on the computer instead of playing football.

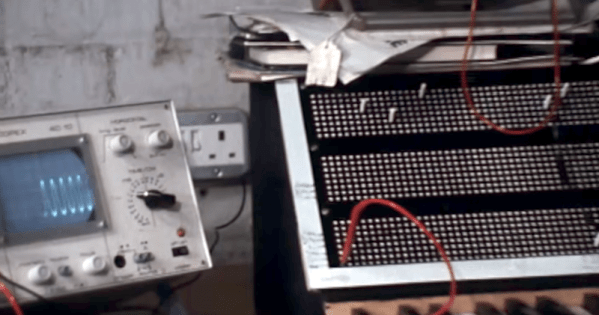

If you want a better look at hardware, around the five-minute mark, you see schoolkids making printed circuit boards, and some truly vintage oscilloscope close-ups. There are plenty of tiny monitors and large, noisy printing terminals.

You have to wonder where the eight-year-olds who learned about computers in the video are today, and what kind of computer they have. They learned binary and the Towers of Hanoi. Their teacher said the kids now knew more about computers than their parents did.

As a future prediction, [James Bellini] did pretty well. Like many forecasters, he almost didn’t go far enough, as we look back almost 50 years. Sure, Prestel didn’t work out as well as they thought, dying in 1994. But he shouldn’t feel bad. Predicting the future is tough. Unless, of course, you are [Arthur C. Clarke].

Continue reading “Retrotechtacular: Computers In Schools? 1979 Says Yes”