Implantable electrodes for the (human) brain have been around for a many decades in the form of Utah arrays and kin, but these tend to be made out of metal, which can cause issues when stimulating the surrounding neurons with an induced current. This is due to faradaic processes between the metal probe and an electrolyte (i.e. the cerebrospinal fluid). Over time this can result in insulating deposits forming on the probe’s surface, reducing their effectiveness.

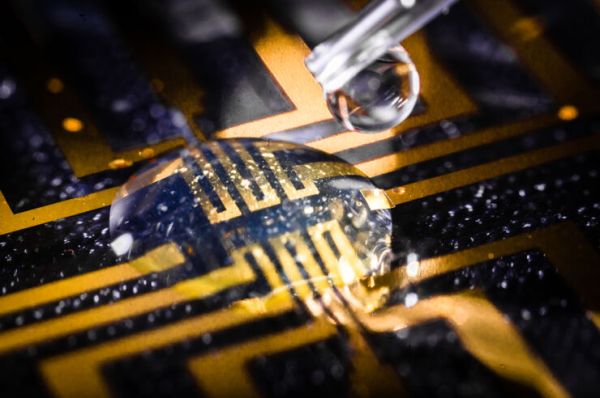

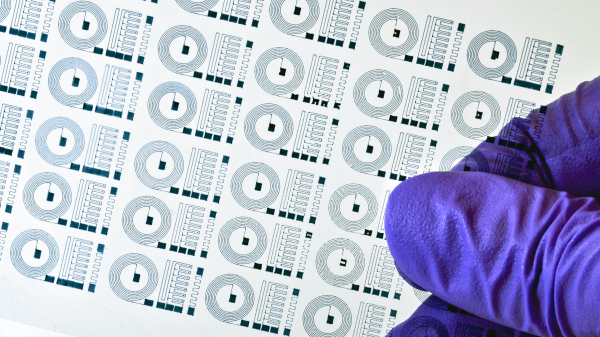

Now a company called InBrain claims to have cracked making electrodes out of graphene, following a series of tests on non-human test subjects. Unlike metal probes, these carbon-based probes should be significantly more biocompatible even when used for brain stimulation as with the target goal of treating the symptoms associated with Alzheimer’s.

During the upcoming first phase human subjects would have these implants installed where they would monitor brain activity in Alzheimer’s patients, to gauge how well their medication is helping with the symptoms like tremors. Later these devices would provide deep-brain stimulation, purportedly more efficiently than similar therapies in use today. The FDA was impressed enough at least to give it the ‘breakthrough device’ designation, though it is hard to wade through the marketing hype to get a clear picture of the technology in question.

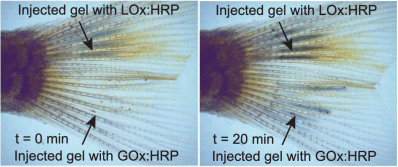

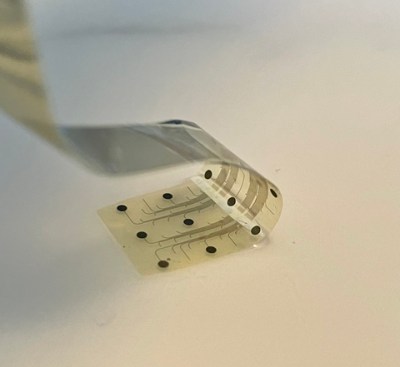

In their most recently published paper (preprint) in Nature Nanotechnology, [Calia] and colleagues describe flexible graphene depth neural probes (gDNP) which appear to be what is being talked about. These gDNP are used in the experiment to simultaneously record infraslow (<0.1 Hz) and higher frequencies, a feat which metal microelectrodes are claimed to struggle with.

Although few details are available right now, we welcome any brain microelectrode array improvements, as they are incredibly important for many types of medical therapies and research.