Here’s a novel ratchet mechanism developed by researchers that demonstrates how a single object — in this case a gear shaped like a six-pointed star — can rectify the disordered energy of its environment into one-way motion.

The Feynman–Smoluchowski ratchet has alternating surface treatments on the sides of its points, accomplished by applying a thin film layer to create alternating smooth/rough faces. This difference in surface wettability is used to turn agitation of surrounding water into a ratcheting action, or one-way spin.

This kind of mechanism is known as an active Brownian ratchet, but unlike other designs, this one doesn’t depend on the gear having asymmetrical geometry. Instead of an asymmetry in shape, there’s an asymmetry in the gear tooth surface treatments. You may be familiar with the terms hydrophobic and hydrophilic, which come down to a difference in surface wettability. The gear’s teeth having one side of each is what rectifies the chaotic agitation of the surrounding water into a one-way spin. Scaled down far enough, these could conceivably act as energy-harvesting micromotors.

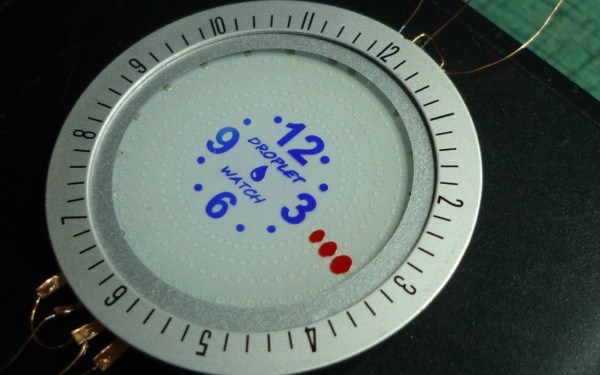

Want more detail? The published paper is here, and if you think you might want to play with this idea yourself there are a few different ways to modify the surface wettability of an object. High voltage discharge (for example from a Tesla coil) can alter surface wettability, and there are off-the-shelf hydrophobic coatings we’ve seen used in art. We’ve even seen an unusual clock that relied on the effect.