Famously, Nikola Tesla won the War of the Currents in the early days of electrification because his AC system could use transformers to minimize losses for long distance circuits. That was well before the invention of the transistor, though, and there are a lot of systems that still use AC now as a result of electricity’s history that we might otherwise want to run on DC in our modern world. Sprinkler systems are one of these things, commonly using a 24V AC system, but [Vinthewrench] has done some work to convert over to a more flexible 24 VDC system instead.

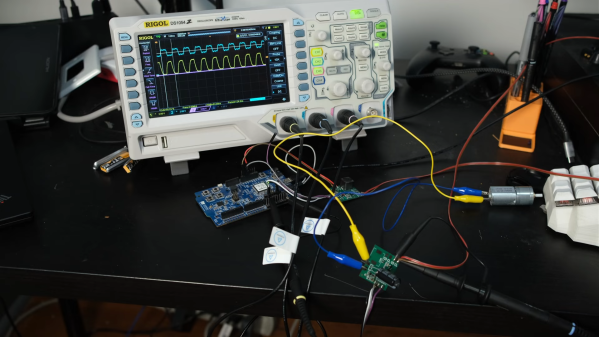

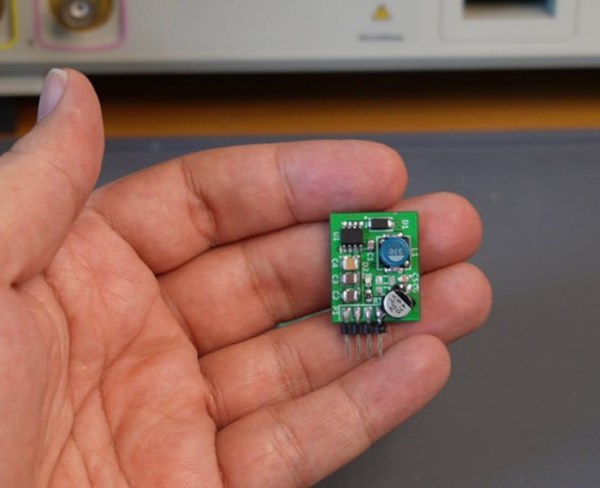

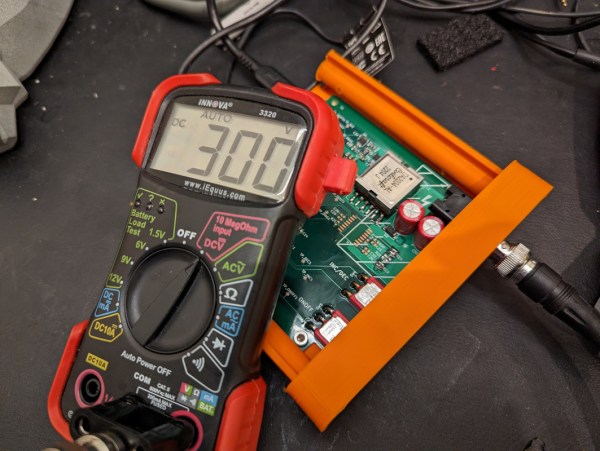

The main components of these systems that are set up for AC are solenoids which activate various sets of sprinklers. But these solenoids can take DC and still work, so no major hardware changes are needed. It’s not quite as simple as changing power supplies, though. The solenoids will overheat if they’re fully powered on a DC circuit, so [Vinthewrench] did a significant amount of testing to figure out exactly how much power they need to stay engaged. Once the math was done, he uses a DRV103 to send PWM signals to the solenoids, which is set up to allow more current to pull in the solenoids and then a lower holding current once they are activated.

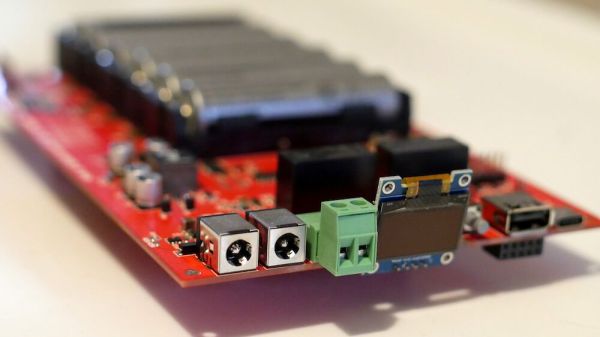

With a DC power supply like this, it makes it much easier to have his sprinkler system run on a solar powered system as well as use a battery backup without needing something like an inverter. And thanks to the DRV103 the conversion is not physically difficult; ensuring that the solenoids don’t overheat is the major concern here. Another great reason to convert to a DIY sprinkler controller is removing your lawn care routine from an unnecessary cloud-based service.