Four years ago when the idea of a pandemic was something which only worried a few epidemiologists, a group of British hardware hackers and robotic combat enthusiasts came up with an idea. They would take inspiration from the American Power Racing Series to create their own small electric racing formula. Hacky Racers became a rougher version of its transatlantic cousin racing on mixed surfaces rather than tarmac, and as an inaugural meeting that first group of racers convened on a cider farm in Somerset to give it a try. Last weekend they were back at the same farm after four years of Hacky Racer development with racing having been interrupted by the pandemic, and Hackaday came along once more to see how the cars had evolved. Continue reading “How Far Can You Push A £500 Small Electric Car; Four Years Of The Hacky Racer”

Hacky Racers4 Articles

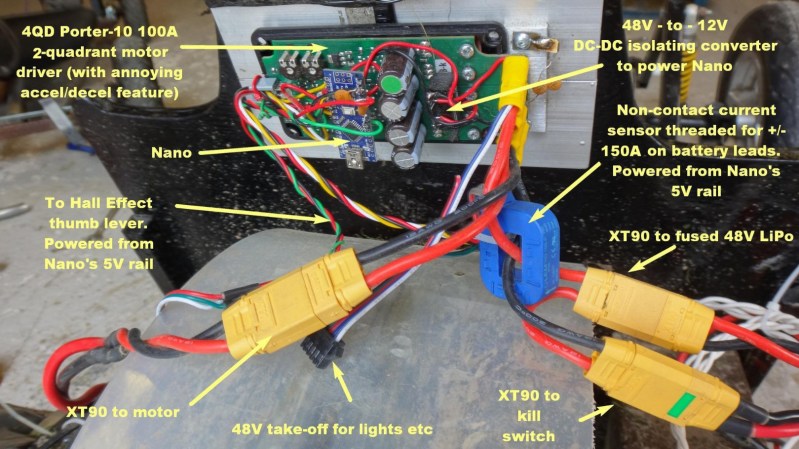

Battle Tested Current Limiter For Cheap DC Motor Controllers

Running a brushed motor in muddy or dusty environments takes a toll on controllers, with both heavy back EMF and high stall currents. This explains one of the challenge in Europe’s Hacky Racer series, which is decidedly more off-road than America’s Power Racing Series.

In pushing these little electric vehicles to the limits, many builders use brushless Chinese scooter motors since they’re both available and inexpensive. Others take the brushed DC route if they’re lucky enough to score a motor — and then the challenge becomes getting the most performance without burning up your controller. To fix this, [MechanicalCat] has come up with a current limiter for cheap DC motor controllers.

The full write-up is in the included PDF file, and describes the set-up of an Arduino Nano sitting between throttle and controller, and taking feedback from a current sensor. The controller in question is a 4QD Porter 10 so an extra component is a DC-to-DC converter to provide a floating ground for the Arduino. However, there is also the intriguing possibility of the same set-up being used with absurdly cheap Chinese motor controllers. There is also advice on fitting flyback diodes, something which might have saved one controller in the Hackaday pits last year.

It’s yet to be seen what effect this will have on Hacky Racer competitiveness, however its applications go far beyond that field into anywhere a reliable small DC motor drive on the cheap is required. Meanwhile, if you’re unsure where this Hacky Racer stuff came from, you could start here.

The Electric Vehicles Of Electromagnetic Field: The Ottermobile And The Ottercar

If you’ve followed these pages over the last few weeks, you’ll have seen an occasional series of posts featuring the comedic electric vehicle creations of the British Hacky Racers series, which will make their debut at the forthcoming Electromagnetic Field hacker camp. So far these intrepid electro-racers have come largely from the UK hackerspace and Robot Wars communities, but it was inevitable that before too long there would arrive some competition from further afield.

[Jana Marie Hemsing] and [Lucy Fauth] are a pair of prolific German hardware hackers whose work you may have seen from time to time in other fields. When they heard about Hacky Racers with barely two weeks until they were due to set off for England for EMF, they knew they had to move fast. The Ottermobile and the Ottercar are the fruits of their labours, and for vehicles knocked together in only two or three days they show an impressive degree of sophistication.

In both cases the power comes courtesy of hoverboard wheels with integrated motors. If you cast your mind back to last year’s SHA Camp in the Netherlands, our coverage had a picture of them on a motorised armchair, so this is a drive system with which they have extensive experience. The Ottercar is based upon a lengthened Kettler kids’ tricycle with the larger variant of the hoverboard motors, and unusually it sports three-wheel drive. Control for the rear pair comes from a hoverboard controller with custom firmware, while the front is supplied by a custom board. The Ottermobile meanwhile is a converted Bobby Car, with hoverboard drive. It’s an existing build that has been brought up to the Hacky Racer rules, and looks as though it could be one of the smaller Hacky Racers.

At the time of writing there is still just about enough time to create a Hacky Racer for Electromagnetic Field. Following the example set from Germany, it’s possible that the hoverboard route could be one of the simplest ways to do it.

The Electric Vehicles Of Electromagnetic FIeld: The Selby

A couple of weekends ago on a farm in rural England with a cider orchard and a very good line in free-range pork sausages, there was the first get-together of the nascent British Hacky Racers series of competitions for comedic small electric vehicles. At the event, [Mark Mellors] shot a set of video interviews with each of the attendees asking them to describe their vehicles in detail, and we’d like to present the first of them here.

The Selby is unique among all the Hacky Racers in being a six-wheeler. It’s the creation of [Michael West] of MK Makerspace, and it bears a curious resemblance to a pair of PowaKaddy golf buggies grafted together. The resulting vehicle has four driven wheels and two steering wheels, and though it is hardly a speedy machine this extra drive gives it what is probably the most hefty pulling power of all the contestants. In the video below it appears without bodywork, but we are told that something impressive will sit upon it when it appears at Electromagnetic Field.

I should own up, that the Selby is a familiar to Hackaday, as I’m also an MK Makerspace member. I’ve seen it progress from two worn-out golf trolleys to its current state, and seen first hand some of the engineering challenges that has presented. The PowaKaddy buggies of that vintage are extremely well-engineered, with a Curtis controller that is still comfortably within spec even when driving four motors instead of two. Unusually for a Hacky Racer the power comes from a pair of huge lead-acid batteries, as these were the power source supplied with the PowaKaddy from new and it made little sense to change them. Gearing is fixed at golf-course speeds, and braking comes from a pair of brakes fitted on the motors. The motors themselves are simple DC affairs, with significant weatherproofing.

Cutting and shutting the two PowaKaddys was straightforward enough, but introduced a warp to the chassis that was solved by your Hackaday scribe hanging on the end of a lever formed from a long piece of 4-by-2 while [Mike] and friends stood on the other end of the Selby.

As a driving experience it’s exciting enough but lacks the speed of some of its competitors. Where it really comes into its own though is off-road, as the multi-wheel drive and broad treaded tyres power it across mud and offer powersliding opportunities on wet grass.

We’ve covered a couple of Hacky Racers so far in our mini-series on the Electric Vehicles of Electromagnetic Field, and we’ll bring you a few more before the event. Meanwhile feast your eyes on a Sinclair C5, and an Austin 7 inspired mobility scooter conversion.

Continue reading “The Electric Vehicles Of Electromagnetic FIeld: The Selby”