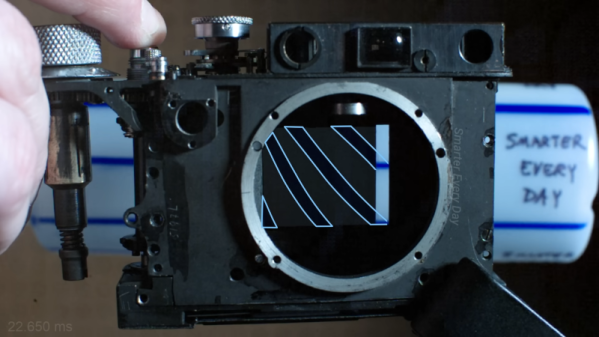

If you are manufacturing something, you have to test it. It wouldn’t do, for example, for your car to say it was going 60 MPH when it was really going 90 MPH. But if you were making a classic Leica camera back in the early 20th century, how do you measure a shutter that operates at 1/1000 of a second — a millisecond — without modern electronics? The answer is a special stroboscope that would look at home in any cyberpunk novel. [SmarterEveryDay] visited a camera restoration operation in Finland, and you can see the machine in action in the video below.

The machine has a wheel that rotates at a fixed speed. By imaging a pattern through the camera, you can determine the shutter speed. The video shows a high-speed video of the shutter operation which is worth watching, and it also explains exactly how the rotating disk combined with the rotating shutter allows the measurement. Continue reading “Measuring A Millisecond Mechanically”