In his most recent article, [Ken Shirriff] takes a break from putting ASICs under a microscope, and instead does the same in a proverbial manner with the word ‘mainframe’. Although these days the word ‘mainframe’ brings to mind a lumbering behemoth of a system that probably handles things like finances and other business things, but originally the ‘main frame’ was just one of many ‘frames’. Which brings us to the early computer systems.

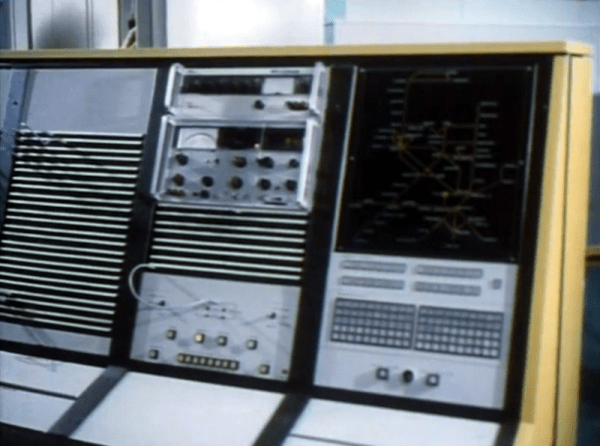

We have all seen the photos of early computer systems, which not only filled rooms, but which also tended to consist of multiple units. This was something which the designers of the IBM 701 computer seem to have come up with, to make it possible to transport and install computer systems without cranes and the breaking out of walls. Within the IBM 701 system’s internal documentation, the unit containing the core logic was referred to as the ‘main frame’, alongside the ‘power frame’, the ‘core frame’, etc.

From this [Ken] then traces how the word ‘main frame’ got reused over the years, eventually making it outside of the IBM world, with a 1978 Radio Electronics magazine defining the ‘mainframe’ as the enclosure for the computer, separating it seemingly from peripherals. This definition seems to have stuck, with BYTE and other magazines using this definition.

By the 1960s the two words ‘main frame’ had already seen itself hyphenated and smushed together into a singular word before the 1980s redefined it as ‘a large computer’. Naturally marketing at IBM and elsewhere leaned into the word ‘mainframe’ as a token of power and reliability, as well as a way to distinguish it from the dinky little computers that people had at home or on their office desk.

Truly, after three-quarters of a century, the word ‘mainframe’ has become a reflection of computing history itself.