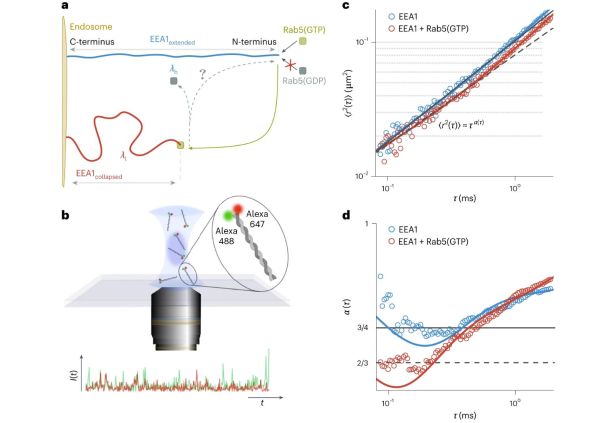

For most of us who haven’t entirely slept through biology classes, it’s probably no secret that ATP (adenosine triphosphate) is the compound which provides the energy needed for us to move our muscles and for our body to maintain and repair itself, yet less know is guanosine triphosphate (GTP). Up till now GTP was thought to be not used for mechanical action like molecular motors, but recent research by Anupam Singh and colleagues in Nature Physics (press release) has shown that two GTPase hydrolase enzymes (Rab5 and EEA1) function effectively as a reversible molecular motor.

Although much of the heavy lifting in the body has shifted to use ATP with ATPases such as myosin and kinesin, GTPases have retained their functional roles in mostly signal transduction (acting as switches or timers), a tethered EEA1 enzyme performs mechanical force when a Rab5 enzyme (in its activated, GTP state) binds to it. Within e.g. a cell this can pull membranes and other structures together. Most importantly, the researchers found that no external influence was necessary for the inactive (GDP) Rab5 enzyme to separate and EEA1 to revert back to its original state, completing a full cycle.

This discovery not only gives us another intriguing glimpse into the inner workings of biological systems, but also increases our understanding of how these molecular motors work, opening intriguing possibilities for constructing our own synthetic structures such as protein engines, where mechanical movement is needed on scales which require such molecular motors.

(Heading image: Binding of the Rab5(GTP) to EEA1 triggers a transition of the EEA1 molecule from a rigid, extended state to a more flexible, collapsed state. (Credit: Anupam Singh et al., 2023) )