[Editor’s Note: After we posted this, we got hit by a comment-report attack, and about 1,000 (!) comments across the whole site got sent back into the moderation queue on Saturday. We’ve since re-instated them all, but that took a lot of work.

About halfway down the comments in this article, the majority of comments are “hey, why did you delete this?” We didn’t, and they should be all good now. We debated removing the “try deleting this!” comments, but since we didn’t delete them in the first place, we thought we should just leave them. It makes a royal mess of any discussion, and created a lot more heat than light, which is unfortunate.]

You know what your mom would say, right? This week, we got an above average number of useless negative comments. A project was described as looking like a “turd” – for the record I love the hacker’s angular and futuristic designs, but it doesn’t have to be to your taste. Then someone else is like “you don’t even need a computer case.” Another commenter informed us that he doesn’t like to watch videos for the thirtieth time. (Yawn!)

What all of these comments have in common is that they’re negative, low value, non-constructive, and frankly have no place on Hackaday. The vast majority are just kind of Eeyorey complaining about how someone else is enjoying a chocolate ice cream, and the commenter prefers strawberry. But then some of them turn nasty. Why? If someone makes a project that you don’t like, they didn’t do it to offend you. Just move on quietly to one you do like. We publish a hack every three hours like a rubidium clockwork, with a couple of original content pieces scattered in-between on weekdays.

And don’t get us wrong: we love comments that help improve a project. There’s a not-so-fine line between “why didn’t you design it with trusses to better hold the load?” and “why did you paint it black, because blue is the superior color”. You know what we mean. Constructive criticism, good. Pointless criticism, bad.

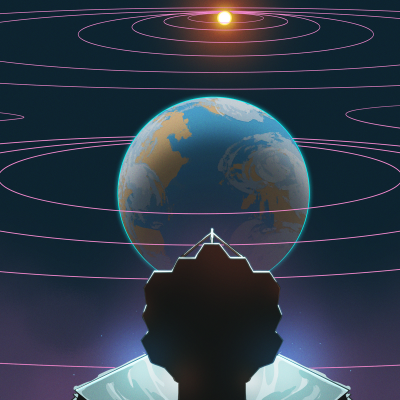

It was to the point that we were discussing just shutting down the comments entirely. But then we got gems! [Maya Posch]’s fantastic explainer about the Lagrange points had an error: one of the satellites that Wikipedia said was at an earth-moon Lagrange point is actually in normal orbit around the moon. It only used the Lagrange point as a temporary transit orbit. Says who? One of the science instrument leads on the space vehicle in question. Now that is a high-value comment, both because it corrects a mistake and enlightens us all, but also because it shows who is reading Hackaday!

It was to the point that we were discussing just shutting down the comments entirely. But then we got gems! [Maya Posch]’s fantastic explainer about the Lagrange points had an error: one of the satellites that Wikipedia said was at an earth-moon Lagrange point is actually in normal orbit around the moon. It only used the Lagrange point as a temporary transit orbit. Says who? One of the science instrument leads on the space vehicle in question. Now that is a high-value comment, both because it corrects a mistake and enlightens us all, but also because it shows who is reading Hackaday!

Or take [Al Williams]’s article on mold-making a cement “paper” airplane. It was a cool technique, but the commenters latched onto his assertion that you couldn’t fly a cement plane, and the discussions that ensued are awesome. Part of me wanted to remind folks about the nice mold-making technique on display, but it was such a joy to go down that odd rabbit hole, I forgive you all!

We have an official “be nice” policy about the comments, and that extends fairly broadly. We really don’t want to hear what you don’t like about someone’s project or the way they presented it, because it brings down the people out there who are doing the hard work of posting their hacks. And hackers have the highest priority on Hackaday.