[HeadlessZeke] was excited to try out his new AT&T wireless cable box, but was quickly dismayed by the required wireless access point that came bundled with it. Apparently in order to use the cable box, you also need to have this access point enabled. Not one to blindly put unknown devices on his network, [HeadlessZeke] did some investigating.

The wireless access point was an Arris VAP2500. At first glance, things seemed pretty good. It used WPA2 encryption with a long and seemingly random key. Some more digging revealed a host of security problems, however.

It didn’t take long for [HeadlessZeke] to find the web administration portal. Of course, it required authentication and he didn’t know the credentials. [HeadlessZeke] tried connecting to as many pages as he could, but they all required user authentication. All but one. There existed a plain text file in the root of the web server called “admin.conf”. It contained a list of usernames and hashed passwords. That was strike one for this device.

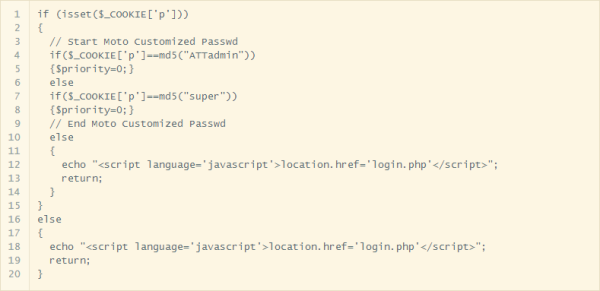

[HeadlessZeke] could have attempted to crack the passwords but he decided to go further down this rabbit hole instead. He pulled the source code out of the firmware and looked at the authentication mechanism. The system checks the username and password and then sets a cookie to let the system know the user is authenticated. It sounds fine, but upon further inspection it turned out that the data in the cookie was simply an MD5 hash of the username. This may not sound bad, but it means that all you have to do to authenticate is manually create your own cookie with the MD5 hash of any user you want to use. The system will see that cookie and assume you’ve authenticated. You don’t even have to have the password! Strike two.

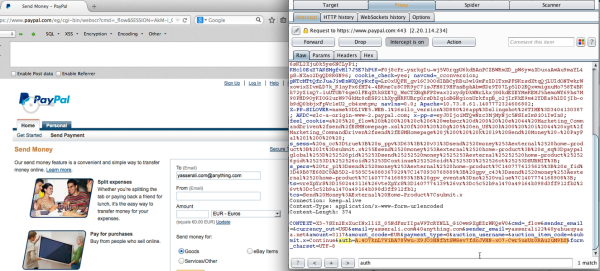

Now that [HeadlessZeke] was logged into the administration site, he was able to gain access to more functions. One page actually allows the user to select a command from a drop down box and then apply a text argument to go with that command. The command is then run in the device’s shell. It turned out the text arguments were not sanitized at all. This meant that [HeadlessZeke] could append extra commands to the initial command and run any shell command he wanted. That’s strike three. Three strikes and you’re out!

[HeadlessZeke] reported these vulnerabilities to Arris and they have now been patched in the latest firmware version. Something tells us there are likely many more vulnerabilities in this device, though.

[via Reddit]