If you ever looked at a PCI to PCIe x16 adapter and wondered what’d happen if you were to stick a modern PCIe GPU in it, the answer apparently is ‘it works’ according to an attempt by [Circuit Rewind]. As long as you accept needing to supply external power with even a low-end GT 1030 card – as the PCI slot cannot provide enough power – and being limited to a single PCIe lane. This latter point isn’t so much of an issue as a single PCIe lane offers more bandwidth than the (shared) PCI bus anyway.

Despite the somewhat improvised setup, the GT 1030 card provided a decent 1080p experience in a range of games, after removing half of the 8 GB of system RAM before the configuration would work, probably due to VRAM mapping issues. Since the mainboard used also offered PCIe, the same card was run in a PCIe x4 slot, as well as in an x1 configuration, both with noticeably higher performance and putting the ‘why’ in ‘try’.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, a RTX 3080 also booted fine with external power and only 4 GB system RAM installed. Despite the PCIe x1 link, the system was able to finish a 3D benchmark and play Doom 2016, but with only 4 GB of system RAM and an old Athlon quad-core CPU, it was a terrible experience. Perhaps the most fascinating lesson to learn from this is that PCI and PCIe are amazingly compatible with only a simple translation bridge, even if high-performance graphics aren’t quite what PCI was meant for. After all, that’s why we got cursed with AGP for many years.

Continue reading “Running A Modern Graphics Card In A 33 MHz PCI Slot”

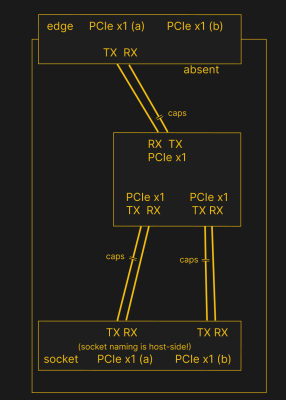

PCIe needs TX pairs connected to RX on another end, like UART – and this is non-negotiable. Connectors will use host-side naming, and vice-versa. As the diagram demonstrates, we connect the socket’s TX to chip’s RX and vice-versa; if we ever get confused, the laptop schematic is there to help us make things clear. To sum up, we only need to flip the names on the link coming to the PCIe switch, since the PCIe switch acts as a device on the card; the two links from the switch go to the E-key socket, and for that socket’s purposes, the PCIe switch acts as a host.

PCIe needs TX pairs connected to RX on another end, like UART – and this is non-negotiable. Connectors will use host-side naming, and vice-versa. As the diagram demonstrates, we connect the socket’s TX to chip’s RX and vice-versa; if we ever get confused, the laptop schematic is there to help us make things clear. To sum up, we only need to flip the names on the link coming to the PCIe switch, since the PCIe switch acts as a device on the card; the two links from the switch go to the E-key socket, and for that socket’s purposes, the PCIe switch acts as a host.

You might have heard the term “bifurcation” if you’ve been around PCIe, especially in mining or PC tinkering communities. This is splitting a PCIe slot into multiple PCIe links, and as you can imagine, it’s quite tasty of a feature for hackers; you don’t need any extra hardware, really, all you need is to add a buffer for REFCLK. See, it’s still needed by every single extra port you get – but you can’t physically just pull the same clock diffpair to all the slots at once, since that will result in stubs and, consequently, signal reflections; a REFCLK buffer chip takes the clock from the host and produces a number of identical copies of the REFCLK signal that you then pull standalone. You might have seen x16 to four NVMe slot cards online – invariably, somewhere in the corner of the card, you can spot the REFCLK buffer chip. In a perfect scenario, this is all you need to get more PCIe out of your PCIe.

You might have heard the term “bifurcation” if you’ve been around PCIe, especially in mining or PC tinkering communities. This is splitting a PCIe slot into multiple PCIe links, and as you can imagine, it’s quite tasty of a feature for hackers; you don’t need any extra hardware, really, all you need is to add a buffer for REFCLK. See, it’s still needed by every single extra port you get – but you can’t physically just pull the same clock diffpair to all the slots at once, since that will result in stubs and, consequently, signal reflections; a REFCLK buffer chip takes the clock from the host and produces a number of identical copies of the REFCLK signal that you then pull standalone. You might have seen x16 to four NVMe slot cards online – invariably, somewhere in the corner of the card, you can spot the REFCLK buffer chip. In a perfect scenario, this is all you need to get more PCIe out of your PCIe.