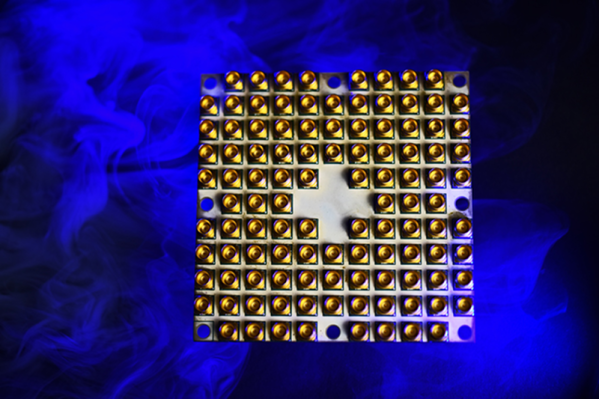

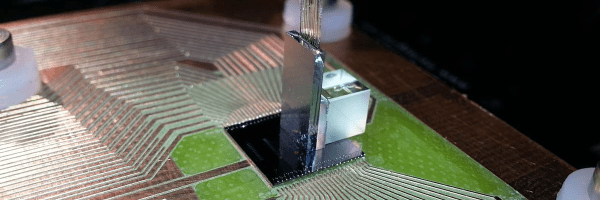

With a backdrop of security and stock trading news swirling, Intel’s [Brian Krzanich] opened the 2018 Consumer Electronics Show with a keynote where he looked to future innovations. One of the bombshells: Tangle Lake; Intel’s 49-qubit superconducting quantum test chip. You can catch all of [Krzanch’s] keynote in replay and there is a detailed press release covering the details.

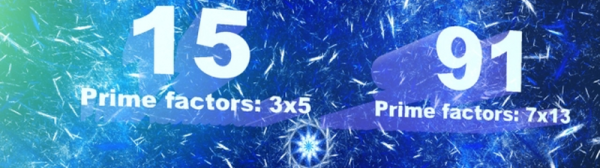

This puts Intel on the playing field with IBM who claims a 50-qubit device and Google, who planned to complete a 49-qubit device. Their previous device only handled 17 qubits. The term qubit refers to “quantum bits” and the number of qubits is significant because experts think at around 49 or 50 qubits, quantum computers won’t be practical to simulate with conventional computers. At least until someone comes up with better algorithms. Keep in mind that — in theory — a quantum computer with 49 qubits can process about 500 trillion states at one time. To put that in some apple and orange perspective, your brain has fewer than 100 billion neurons.

Of course, the number of qubits isn’t the entire story. Error rates can make a larger number of qubits perform like fewer. Quantum computing is more statistical than conventional programming, so it is hard to draw parallels.

We’ve covered what quantum computing might mean for the future. If you want to experiment on a quantum computer yourself, IBM will let you play on a simulator and on real hardware. If nothing else, you might find the beginner’s guide informative.

Image credit: [Walden Kirsch]/Intel Corporation