The Raspberry Pi 4 was just released. This is the newest version of the Raspberry Pi and offers a better CPU and more memory than the Raspberry Pi 3, dual HDMI outputs, better USB and Ethernet performance, and will remain in production until January, 2026.

There are three varieties of the Raspberry Pi 4 — one with 1GB of RAM, one with 2GB, and one with 4GB of RAM — available for $35, $45, and $55, respectively. There’s a video for this Raspberry Pi launch, and all of the details are on the Raspberry Pi 4 website.

A Better CPU, Better Graphics, and More Memory

The CPU on the new and improved Raspberry Pi 4 is a significant upgrade. While the Raspberry Pi 3 featured a Broadcom BCM2837 SoC (4× ARM Cortex-A53 running at 1.2GHz) the new board has a Broadcom BCM2711 SoC (a quad-core Cortex-A72 running at 1.5GHz). The press literature says this provides desktop performance comparable to entry-level x86 systems.

Of note, the new Raspberry Pi 4 features not one but two HDMI ports, albeit in a micro HDMI format. This allows for dual-display support at up to 4k60p. Graphics power includes H.265 4k60 decode, H.264 1080p60 decode, 1080p30 encode, with support for OpenGL ES, 3.0 graphics. As with all Raspberry Pis, there’s a component composite video port as well tucked inside the audio port. The 2-lane MIPI DSI display port and 2-lane MIPI CSI camera port remain from the Raspberry Pi 3.

Continue reading “Raspberry Pi 4 Just Released: Faster CPU, More Memory, Dual HDMI Ports”

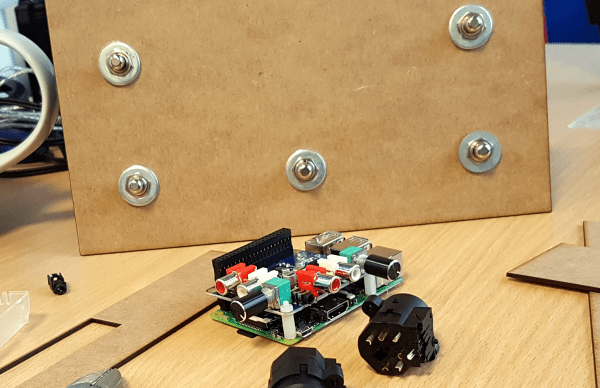

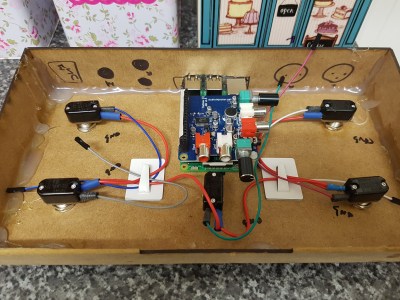

At the center of the box is a Raspberry Pi with an AudioInjector stereo sound card. The card takes care of stereo in and out, and passing the signal to the Pi. The software is Modep, an open source audio processor that allows the setup of a chain of digital effects plugins to be run on the Pi. After finding some foot switches, [Craig] connected them to an Arduino Pro Micro which he set up as a MIDI device that sends MIDI messages to the Modep software running on the Pi.

At the center of the box is a Raspberry Pi with an AudioInjector stereo sound card. The card takes care of stereo in and out, and passing the signal to the Pi. The software is Modep, an open source audio processor that allows the setup of a chain of digital effects plugins to be run on the Pi. After finding some foot switches, [Craig] connected them to an Arduino Pro Micro which he set up as a MIDI device that sends MIDI messages to the Modep software running on the Pi.