[Spode] has been rocking out with a pair of Shure E4C earphones for about six years now, and he has no intentions of buying another set any time soon. The earphones cost him £200, so when the right channel started acting up, he decided to fix them rather than toss them in the trash bin.

His first attempt was successful, but just barely so. He ended up damaging the earphone case pretty badly, and in time the same problem reappeared. Undeterred, he opted to fix them once again, but this time around he did things differently.

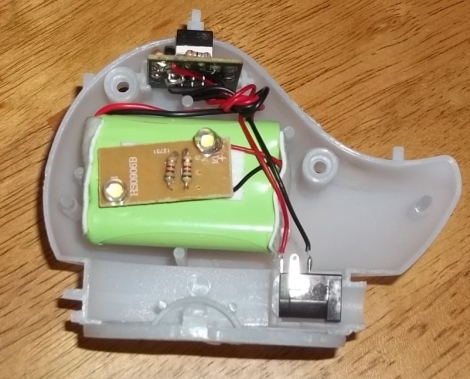

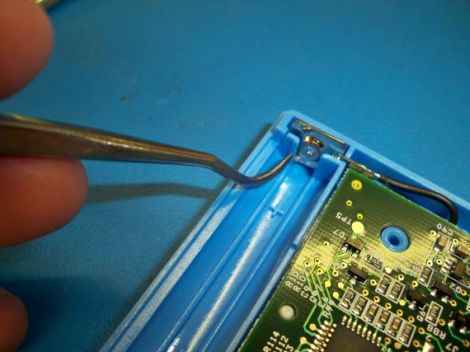

Upon disassembling them, he found that his repair job had become frayed over time. [Spode] desoldered both drivers from the wires and cut them back a bit to expose some nice clean (and structurally sound) cable. He spent a little more time carefully soldering things back together to mitigate the chances of having to repair them again before replacing both earphone shells with a bit of black Sugru.

Having saved himself £200, [Spode] is quite happy with the repair. We probably would have tied an underwriter’s knot in each cable before soldering them to the drivers in the name of strain relief, though the Sugru should help with that.