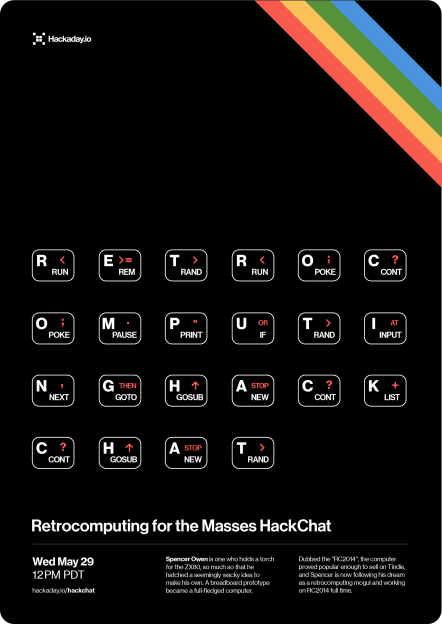

Join us on Wednesday 29 May 2019 at noon Pacific for the Retrocomputing for the Masses Hack Chat!

Of the early crop of personal computers that made their way to market before IBM and Apple came to dominate it, few machines achieved the iconic status that the Sinclair ZX80 did.

Of the early crop of personal computers that made their way to market before IBM and Apple came to dominate it, few machines achieved the iconic status that the Sinclair ZX80 did.

Perhaps it was its unusual and appealing design style, or maybe it had more to do with its affordability. Regardless, [Sir Clive]’s little machine sold north of 100,000 units and earned a place in both computing history and the hearts of early adopters.

Spencer Owen is one who still holds a torch for the ZX80, so much so that in 2013, he hatched a seemingly wacky idea to make his own. A breadboard prototype of the Z80 machine slowly came to life over Christmas 2013, one thing led to another, and the “RC2014” was born.

The RC2014 proved popular enough to sell on Tindie, and Spencer is now following his dream as a retrocomputing mogul and working on RC2014 full time. He’ll be joining us to discuss the RC2014, how it came to be, and how selling computing nostalgia can be more than just a dream.

Our Hack Chats are live community events in the Hackaday.io Hack Chat group messaging. This week we’ll be sitting down on Wednesday May 29 at 12:00 PM Pacific time. If time zones have got you down, we have a handy time zone converter.

Our Hack Chats are live community events in the Hackaday.io Hack Chat group messaging. This week we’ll be sitting down on Wednesday May 29 at 12:00 PM Pacific time. If time zones have got you down, we have a handy time zone converter.

Click that speech bubble to the right, and you’ll be taken directly to the Hack Chat group on Hackaday.io. You don’t have to wait until Wednesday; join whenever you want and you can see what the community is talking about.