Interesting parts make for interesting projects, and this nifty precision voltage reference has some pretty cool parts, not to mention an interesting test jig.

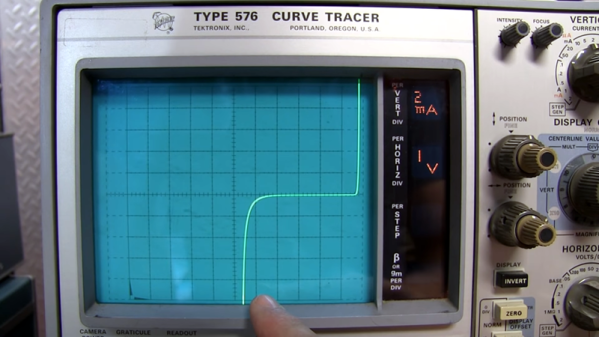

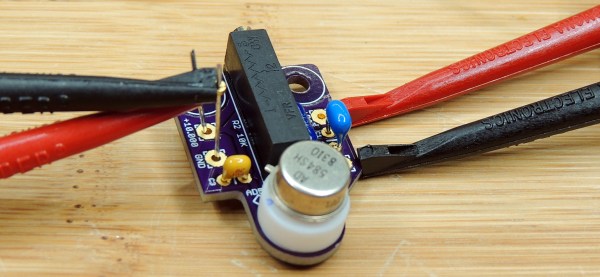

The heart of [Gaurav Singh]’s voltage reference is an ADR1399, precision shunt reference from Analog Devices. The datasheet makes for pretty good reading and reveals that there’s a lot going on inside the TO-49 case, which looks unusually large thanks to a thick plastic coat. The insulation is needed for thermal stability for the heated Zener diode reference. The device also has a couple of op-amps built in, one that provides closed-loop voltage control and another that keeps the internal temperature at a toasty 95°C. The result is a reference that’s stable over a wide range of operating conditions.

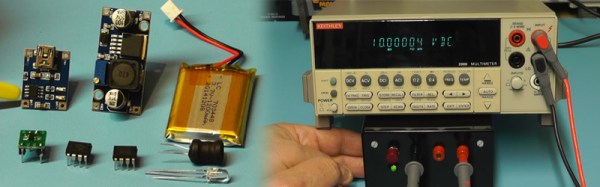

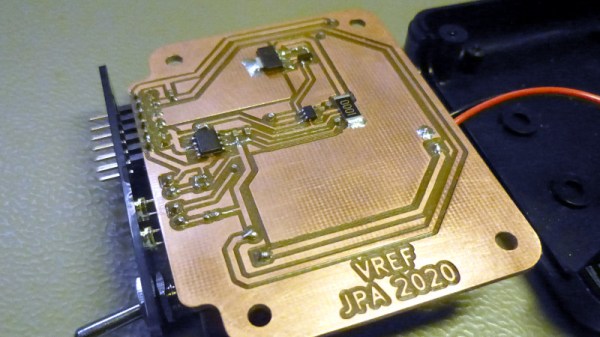

[Gaurav]’s implementation maximizes this special part’s capabilities while making it convenient to use. The PCB has a precision linear regulator that accepts an input voltage from 16 V to 20 V, plus a boost converter that lets you power it from USB-C. The board itself is carefully designed to minimize thermal and mechanical stress, with the ADR1399 separated from the bulk of the board with wide slots. The first video below covers the design and construction of an earlier rev of the board.

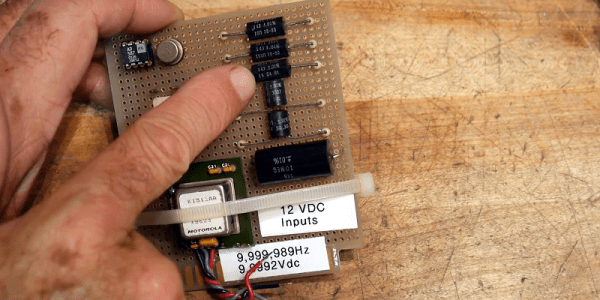

One problem that [Gaurav] ran into with these boards was the need to age the reference with an extended period of operation. To aid in that, he built a modular test jig that completed PCBs can be snapped into for a few weeks of breaking in. The jigs attach to a PCB with pogo pins, which mate to test points and provide feedback on the aging process. See the second video for more details on that.

Continue reading “Precision Reference Puts Interesting Part To Work”

The

The