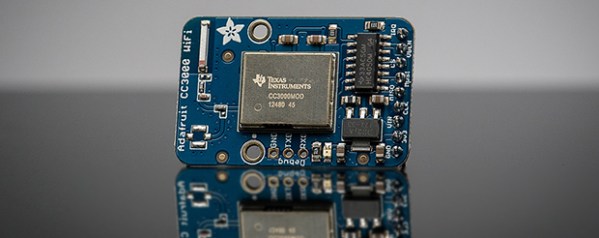

Over the last few months, a few very capable hackers have had a hand in cracking open a Transcend WiFi-enable SD card that just happens to be running a small Linux system inside. The possibilities for a wireless Linux device you can lose in your pocket are immense, but so far no one has gotten any IO enabled on this neat piece of hardware. [CNLohr] just did us all a favor with his motherboard for these Transcend WiFi SD cards, allowing the small Linux systems to communicate with I2C devices.

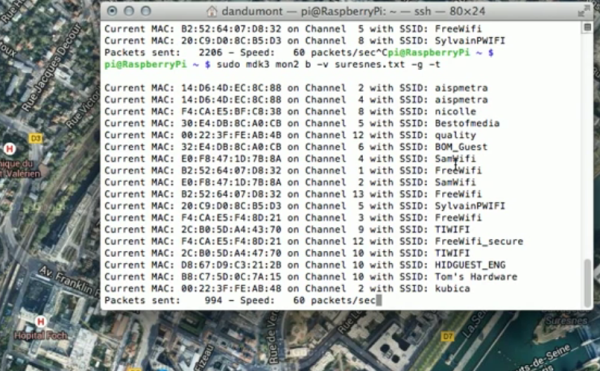

This build is based upon [Dmitry]’s custom kernel for the Transcend WiFiSD card. [CNLohr] did some poking around with this system and found he could use an AVR to speak to the card in its custom 4-bit protocol.

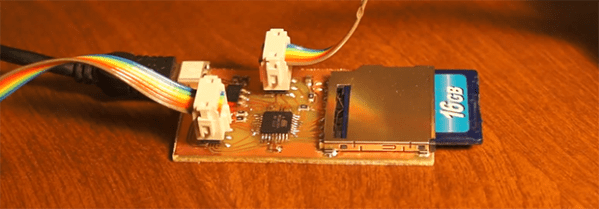

The ‘motherboard’ consists of some sort of ATMega, an AVR programming header, a power supply, and a breakout for the I2C bus. [Lohr] wired up a LED array to the I2C bus and used it to display some configuration settings for the WiFi card before connecting to the card over WiFi and issuing commands directly to the Linux system on the card. The end result was, obviously, a bunch of blinking LEDs.

While this is by far the most complex and overwrought way to blink a LED we’ve ever seen, this is a great proof of concept that makes the Transcend cards extremely interesting for a variety of hardware projects. If you want your own Transcend motherboard, [CNLohr] put all the files up for anyone who wants to etch their own board.