An Instruction Set Architecture (ISA) defines the software interface through which for example a central processor unit (CPU) is controlled. Unlike early computer systems which didn’t define a standard ISA as such, over time the compatibility and portability benefits of having a standard ISA became obvious. But of course the best part about standards is that there are so many of them, and thus every CPU manufacturer came up with their own.

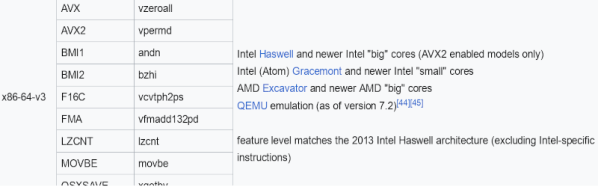

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the number of mainstream ISAs dropped sharply as the computer industry coalesced around a few major ones in each type of application. Intel’s x86 won out on desktop and smaller servers while ARM proclaimed victory in low-power and portable devices, and for Big Iron you always had IBM’s Power ISA. Since we last covered the ISA Wars in 2019, quite a lot of things have changed, including Apple shifting its desktop systems to ARM from x86 with Apple Silicon and finally MIPS experiencing an afterlife in the form of LoongArch.

Meanwhile, six years after the aforementioned ISA Wars article in which newcomer RISC-V was covered, this ISA seems to have not made the splash some had expected. This raises questions about what we can expect from RISC-V and other ISAs in the future, as well as how relevant having different ISAs is when it comes to aspects like CPU performance and their microarchitecture.

Continue reading “Checking In On The ISA Wars And Its Impact On CPU Architectures”