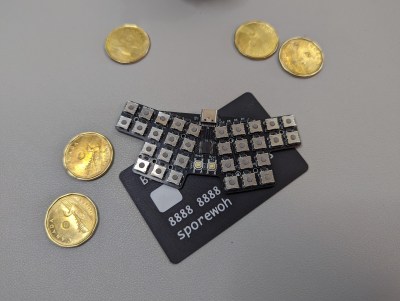

Well, here’s a fresh idea! [flurpyflurples] is back from hiatus with the Mintboard, a 40% that fits inside of an Altoids tin. Who could ask for more than a rugged little Bluetooth keyboard with a built-in cover that fits in your pocket?

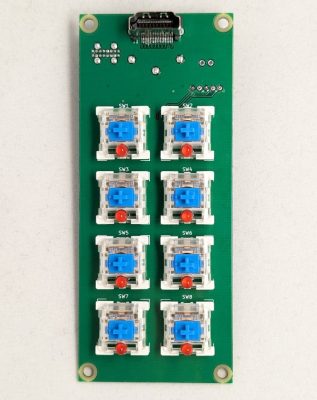

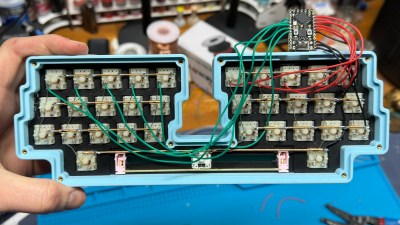

This build started with meticulously measuring the tin to figure out what kind of switches could be used. At first, this was going to be a 60% keyboard, but after a lot of design decisions and switch comparisons, [flurpyflurples] settled on a certain micro switch spaced at 7.3mm for a 40% layout. Then it was time to design a PCB.

Although [flurpyflurples] tends to use Arduino Pro Micros in their builds, they went with the Nice! Nano this time for the Bluetooth capabilities. This means that they had to program it with ZMK instead of QMK, but found that QMK knowledge transfers rather nicely.

Although [flurpyflurples] tends to use Arduino Pro Micros in their builds, they went with the Nice! Nano this time for the Bluetooth capabilities. This means that they had to program it with ZMK instead of QMK, but found that QMK knowledge transfers rather nicely.

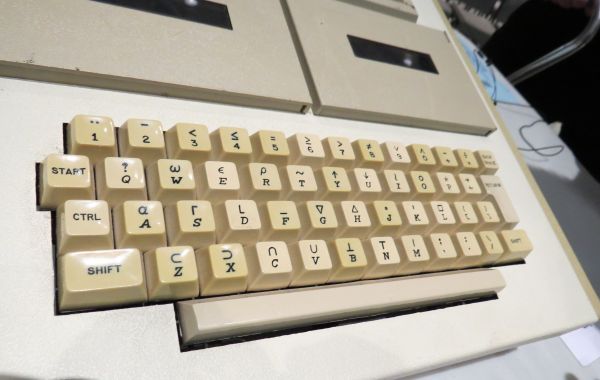

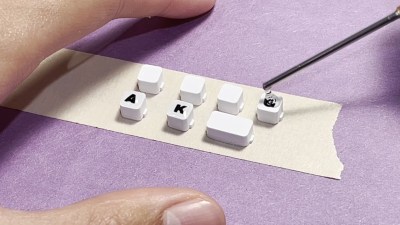

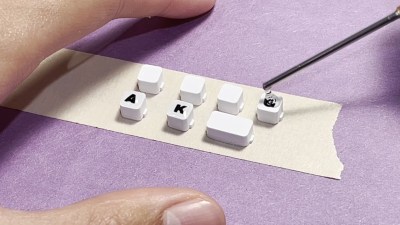

Let’s talk about those lovely legends. The keycaps are 3D printed of course, and the legends were cut out on a Cricut machine. The best part is that sealant — [flurpyflurples] used a few drops of UV nail polish top coat and cured it with light.

We think this looks and sounds fantastic, and would really like to know how to get such clean cutouts. According to [flurpyflurples] and the end of the build/demo video you’ll find below the break, the action is a lot like a Blackberry keyboard.

Continue reading “Altoids Tin Keyboard Is A Breath Of Fresh Air” →